A streamlining solution for crime manufacturers

Has your city’s containment zone reached peak efficiency?

Hello! Happy Sunday! This newsletter recently hit the 700 club! It’s a crazy milestone for me, and I’m happy to say that in almost Year 4 of this newsletter, it’s still growing. Currently sitting at 706 paid subscribers and 3,825 overall subscribers. So hopefully soon I’ll be posting about the Big 4000!! Anyway, I’m very stoked on all this, and grateful. Thank you to everyone who makes this thing possible.

The main piece today is about Shotspotter. It’s a proper “deep dive” and it was a collaboration! Me and Chris Robarge teamed up to write it together, since we were both champing at the bit to take a crack at the recent news. The end result is a pretty cool mind-meld. Proud of this one! Much to think about.

A streamlining solution for crime manufacturers

By Bill Shaner and Chris Robarge

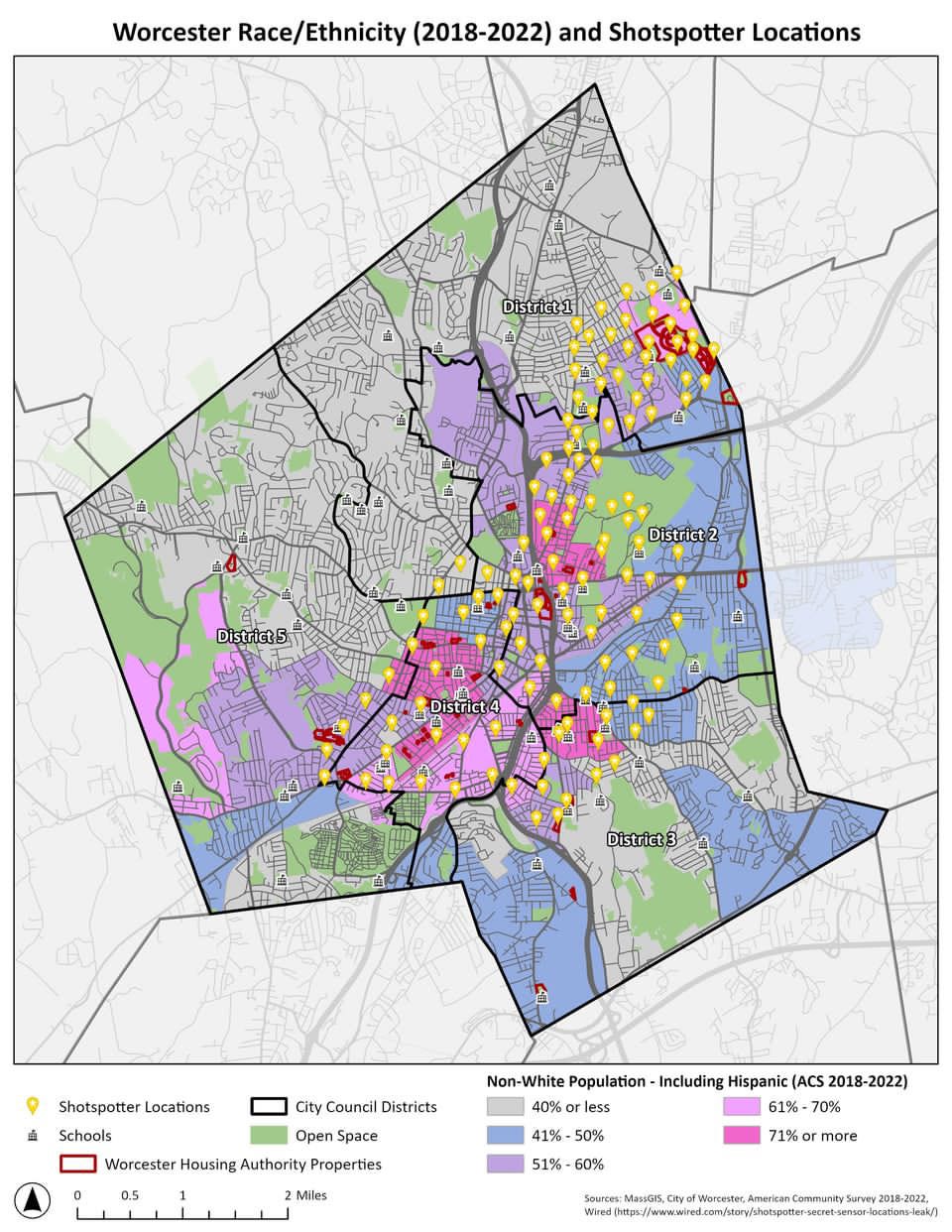

The recent leak of Shotspotter microphone locations in cities across America–including Worcester, of course–exposed a clear racial and class bias in the deployment of a new and untested policing technology. But it would be reductive to pin that bias on the company itself. What we’re seeing in these leaks is just a new and particularly vivid illustration of an old thing. It’s merely a glimpse at where the true violence of American policing has always been meted out, and where it hasn’t.

When departments like Worcester contracted this technology, they put in motion a process of telling on themselves, culminating in these leaked documents. In a uniquely acute way, the maps show a city’s containment zone—the quiet project of American policing said out loud, and with novel clarity.

When the Wired investigation—“Here Are the Secret Locations of ShotSpotter Gunfire Sensors”—hit last week, it made public a lot of internal Shotspotter data that had previously been secret. It showed that more than more than 12 million Americans live in neighborhoods with at least one ShotSpotter sensor, and that those millions of Americans tended to be people of color.

An analysis of sensor distribution in US cities in the leaked data set found that, in aggregate, nearly 70 percent of people who live in a neighborhood with at least one SoundThinking sensor identified in the ACS data as either Black or Latine. Nearly three-quarters of these neighborhoods are majority nonwhite, and the average household earns a little more than $50,000 a year.

The Wired story includes a map of all the mic locations in every city that has them. A friend of the newsletter who would rather stay anonymous made some handy overlays of those locations in Worcester and demographic maps.

Here’s one for race.

And here’s one for income.

What you’re looking at here is Worcester’s containment zone!

Shotspotter isn’t very good at its stated purpose. The technology, billed as a “gunshot detection system,” is ineffective and redundant. It hasn’t figured out fireworks yet, for instance. Or backfiring car engines. The grift of it is obvious, as is the fact the cops are in on the ruse.

On the other hand, it’s very good at demonstrating unspoken base functions of police departments, especially urban ones. The microphones are placed where “crime” happens. Where “crime” is expected. The microphones generate more of this “crime”—but not in the typical use of the word. “Crime” in much of this story means “crime data.” It’s violence that only exists in spreadsheets and databases.

In Worcester and seemingly every other city, the map of mic locations is a strikingly precise mirror of where the poor and brown people live. The mics are not placed where “crime” is unexpected. The areas that are whiter, more wealthy, more “suburban” have no microphones.

According to the Wired story, the company determines mic locations using data they receive from the police:

The company asks police departments who purchase its system for data about gun violence, which Chittum characterizes as objective, to recommend a general plan for sensor placement. Once a plan is agreed upon by the department, the company will seek permission from private property owners, utility companies, and businesses to install sensors on their premises.

It just so happens that, as a result of this process, the mics end up in the poorest and most diverse neighborhoods! And not in the richer, whiter ones. The placements reflect a bias that already existed.

In an effort to achieve a technocratic sort of efficiency—letting data dictate where the mics go and where they don’t—the company and the police departments that contract its services effectively told on themselves. The containment zones maintained by urban police departments across America have never been so clearly outlined. Shotspotter didn’t make racist or classist decisions in placing these microphones–it collected, analyzed, and synthesized all the racism and classism built into police work. In shooting for peak analytic efficiency, it created a stark new portrait of an old reality—one the police do their best to deny.

One of the uncomfortable and often unsaid realities confirmed by these maps is that police exist to maintain the containment zones. That’s an increasingly non-controversial idea—what we mean when we say “overpoliced neighborhoods.”

More uncomfortable still, they demonstrate a function that’s deeper and more central to police work. The police manufacture crime. That is the central mandate of American police departments. They do not fight crime. They make it. I’m nervous I’ll lose some people for flatly saying that. But it’s not crazy. It’s clarifying. Once you see it that way, you can’t unsee it. And Shotspotter is fantastic for the purpose of making the case. That’s the idea we’re going to focus on today.

In the Shotspotter story, we see a seismic collision. The tech sector, with its need to harvest data and generate analytics, smashes into law enforcement, with its incentive to maintain the perception that the floor is the ceiling while smashing us into it. The data analysis that makes the tech efficient makes the lying and propagandizing harder to sell. The contradiction is a big one! And these leaked documents make it easy to see.

Before it’s anything else, Shotspotter is a product that exists in a marketplace. The company, which renamed itself SoundThinking last year, is publicly traded. The value of its products is defined by the problem they identify and the solution they offer. Same as TurboTax or QuickBooks or Robinhood, just for a more specific customer.

What is the problem that Shotspotter identifies? That’s an important and very open question.

In marketing material, the gunshot detection software promises to “save lives and find critical evidence.” Gun violence is an epidemic, they say, before delivering the marquee data point of the pitch: “80 percent of shootings are NEVER called in.”

Left unaddressed is the simple fact that detecting a gunshot does not prevent the gunshot. It’s a thin premise to suggest the gun violence epidemic is driven by insufficient 911 calls about gun violence.

“Criminals are evolving, so we have to evolve too. Be proactive against gun violence with ShotSpotter.”

Cue the Tim Robinson meme: You sure about that? You sure about that’s what “proactive” means?

It’s simply not. It’s not even intended to be proactive. At best, it improves the ability to react. But, as we’ll get to later, there’s not a lot of evidence to suggest it accomplishes even that.

So, let’s explore the idea that maybe “safety” isn’t the real problem they’re trying to solve. Maybe it’s not the “gun violence epidemic.” Maybe it’s another problem—one that isn’t as nice to say out loud, perhaps.

Look instead at the shotspotter product from the perspective I (Bill) suggested earlier. The manufacturing crime perspective. Even if you don’t believe there’s merit to that idea, just try it on for a second. A thought exercise. Purely rhetorical.

If the cops want to create more crime, what then is Shotspotter’s sales pitch? What is the problem and the solution? It’s pretty obvious, I think. Streamlining! Efficiency! Within this premise, Shotspotter is all of a sudden using a familiar line. Employing technology to increase efficiency. Like Slack. It makes a workplace more productive. It makes crime easier to manufacture. There are more (alleged) gunshots on record. More responses. More evidence for more charges. More reasons to stop people. Question them. Pat and frisk them! Initiate more confrontations which might lead to more charges. More work to do! More data points to report! More “crime” logged in the system. More justification for more public money. That is a strong premise, whereas reducing gun violence is a thin one.

If you look at the containment zones as a sort of mine, and the cops as a mining company, and “crime” as the ore, Shotspotter’s true value is its ability to discover new veins. More reason to send more miners down the shaft. More raw crime material for the manufacturing plant.

I think it makes a little bit too much sense to be written off! Something to consider! Does Shotspotter coverage make a neighborhood safer to live in? Or does it make a neighborhood more productive for the crime manufacturers?

It’s The Statistics, Stupid

As far as police departments go, Worcester’s is a useful example insofar as it is run of the mill. The WPD is certainly not known for out of the box thinking or progressive approaches, nor is it remarkably mismanaged or corrupt. It’s both of the latter, of course, but in a par for the course sort of way. It is under DOJ investigation, but so was Springfield, and the potential issues at hand are of the usual sort. Worcester is not notably “dangerous” like the “murder capitals” on the news. But it’s not remarkably “safe,” either. How the WPD operates is how a lot of police departments operate, and it does so in a city that’s neither big nor small. So it’s worth looking at some general themes which underline the appeal of Shotspotter for the WPD and Worcester city hall.

We’re one of about 130 American cities to adopt the Shotspotter technology, and we’ve had it longer than most. First purchasing it in 2013, we’ve had this technology for a decade now. And, as we’ll discuss later, we were also early adopters of a new, AI-based service that Shotspotter offers to “forecast crime,” purchasing it in 2021. A large part of the appeal is the stats it generates, and the WPD brass is all about the stats.

Modern policing in the US has taken a lot of new shapes and forms, but compared to issues like police militarization or surveillance, an under-discussed facet of police work is how statistics have become a driving force. You could argue, and I (Chris) would, that it is one of the main driving forces. Stats determine how much funding and new toys police get, and what they get to do, and whether officers get plush assignments, promotions, and those sweet sweet detail paychecks. Generate the right metrics, and that’s your reward. Don’t generate the right metrics, and your life is made a living hell. Reveal the existence of this system, and you might lose your job and get involuntarily committed! It’s helpful to remember this when you think about why police are so eager to take on new technologies like ShotSpotter. It helps generate stats, and police use those stats to justify both themselves and more technology to generate more stats. It’s the ledger of what they extract in the crime mine.

Stats can also be used to show crime trends moving the way that fits whatever the police narrative is at the time: In New York City among many other places, stats are used not only to justify policies like stop-and-frisk, which generate “crime” statistics, but also to actually systematically under-report crimes like rape. Stats also self-justify because where you police the hardest, you will get the highest crime rates: As one of many examples, Black people and white people use marijuana at roughly the same rate, but Black people are 3.6 times as likely to be arrested for possession. People of color are also the most likely to be cited for so-called “public order” offenses: Public drinking. Loitering. Disorderly conduct and disturbing the peace. Trespass. You get the idea.

Also not unique to Worcester is the fact that there is always a subtle (and sometimes not so subtle!) assurance to the landed and moneyed class that this is not for them and won’t be used where they live. Don’t worry, they only want to use this on the other people! The ones you’re already afraid of! The ones in the “containment zone”. Other police surveillance technologies, such as automatic license plate readers and cameras and actually the police themselves, are similarly deployed to the areas that are mapped above. Actual cops and cruisers are similarly deployed, too, because this is all a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This heavy emphasis on stats is, to my (Bill’s) mind, a confirmation of the idea that cops manufacture crime rather than combat it. In the pursuit of “good numbers” the definition of “crime” is divorced from what a regular person would think of as “safety.” The number of arrests made or guns seized or calls responded to or cases cleared are not useful metrics for a regular person to assess the likelihood of whether something bad will happen to them. Nevertheless, they’re the primary measure by which cops are ostensibly graded by the municipalities that fund them. Accordingly, it matters more that the stats exist than whether they’re good stats.

Shotspotter generates a lot of stats, but there’s a growing volume of research showing that the stats Shotspotter generates are junk. Fuzzy numbers! The sort of bad data that relies on the assurance no one takes a good look under the hood, which of course most people don’t. Especially those who stand to benefit from how they look on paper.

A study by the MacArthur Justice Center of 2019-2021 data from Chicago found that 89 percent of Shotspotter deployments did not lead to evidence of a gun-related crime. There were an average of 61 unfounded deployments each day. There were, however, more than 2,400 stop-and-frisks triggered by the system between 2020 and 2021. The report found that “some officers are relying on ShotSpotter results in the aggregate to provide an additional rationale to initiate a stop or conduct a pat down.”

More trips into the containment zones—and more rationalization for them—while the gun-related evidence that is ostensibly the goal rarely materializes. Meanwhile, more confrontations between containment zone residents and police officers. The numbers are similar in other cities studied, including Atlanta, Dayton, and Houston.

In three separate academic studies carried out between 2018 and 2021, researchers found there was no correlation between use of the technology and firearm crime reduction.

A fact sheet of these studies provided by End Police Surveillance is jarring to read. It takes to task the company’s claim that the technology is 97 percent accurate. It turns out they’ve never tested the system, and only counts the false alarms that a police department takes the time to submit. Doing so is voluntary, of course. And since the supposed gunshot categorically occurred before police officers arrived, who’s to say? It could have been. Can’t prove it wasn’t.

“Nobody has ever done an empirical study of how readily the system is fooled by noises that are not gunfire (i.e. how often it generates false-positive alerts),” the fact sheet reads. There has never been an independent audit, either.

Once you know that Shotspotter’s accuracy is actually not as advertised but completely unknown, it’s funny to look at this chart the company provided Worcester in 2022, which City Manager Ed Augustus included in a report he compiled to show the City Council why Shotspotter is a good thing.

The subhead is the key thing to look at: “New Year’s Eve, New Year’s Day and Independence Day Gunfire Are Excluded.”

Hmmmmmmm what loud noises typically happen on those particular days? And why, if your system is 97 percent accurate, would you exclude the “gunfire” that happens on the days that tend to be the most firework heavy?

It’s cartoonishly obvious they manipulated the data to make it look better. Still, Augustus included it as evidence of what he called, in his introduction, a “strong policing tool” which “allows officers to respond more effectively and efficiently to incidents of gunfire.”

This was a line happily swallowed by almost everyone on the city council, but more on that later.

The more important point is that the Shotspotter-generated stats are obvious junk. Instead of considering that junkiness, officials in cities like Worcester remain content with the fact that they’re stats. They do so because the stats are more important to them than what the stats mean. The data doesn’t have to be good for it to help the cops manufacture more crime.

Examples of cities that have taken Shotspotter to task are few and far between. Worcester certainly hasn’t. But that tide might be turning.

The Chicago Exception

A few weeks ago, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson announced he would not be renewing the city’s contract with the company. When the contract expires in September, the city will decommission the technology. It became the latest and largest of a small handful of cities thathave parted ways with the company (fun fact: Fall River, MA is one of them).

In ending the deal, he was making good on a campaign promise. In Chicago’s local politics, there’s been considerable pressure to get rid of it. There’s a coalition called Stop Shotspotter. A member of the coalition was quoted in the Chicago Sun Times saying they were able to pressure city officials to a “pont where a decision had to be made.” Mayor Johnson, for his part, said he’d rather take the $49 million Chicago gives Shotspotter and put it toward “new resources that go after illegal guns without physically stopping and frisking Chicagoans on the street.”

The cops there aren’t happy, of course. Police union officials are quoted in the same story with fear-mongering allegations that losing Shotspotter will “hurt the city.” But the political pressure of advocates won out over the pressure of the cops in this instance.

While encouraging news, it’s not an easy thing to pull off. It’s not every day that a city administration breaks with the police to respond to the people. It’s very hard to imagine it happening in Worcester, as is likely the case in most cities with Shotspotter contracts.

It's worth laying out why what happened in Chicago seems so impossible in Worcester. So a trip down memory lane is in order–back to 2013, when the first contract was signed.

The Shotspotter Decade

The council vote to purchase Shotspotter in 2013 was unanimous and, per tradition, councilors took it as an opportunity to lavish praise on the police. There was no significant pushback, either to the initial proposal or the “East Side expansion” tacked on, funded by incoming cash from the new CSX railyard. (This is money that could have gone to any number of more deserving services). In total, it cost about $850,000 to get Shotspotter up and running, according to a Telegram story from the time. The funding was also approved unanimously. In the minutes, there’s no record of a discussion. The Telegram notes that the entire police command staff attended the meeting to “show support” for the purchase. One could interpret such a display as more threatening than supportive... but hey. Who’s to say, right? No one on the City Council was opposed, after all.

Over the years that followed, there were only a few passing moments of discussion on the council floor, and not especially heated ones.

It wasn’t until 2021 that Shotspotter came back into the public discourse in a significant way. This time, there was opposition. A lot, actually. Not that it mattered. The council voted 8-3 to expand their contract with Shotspotter to employ so-called “predictive policing,” an AI tool for assigning the routes of patrols. I’ll give you one guess where that AI is sending the patrols! The containment zone, folks.

We still know very little about this predictive policing software and how the WPD uses it. They also voted to allow the manager to take $148,000 out of a contingency fund to buy it. Giving the cops a new “tool” was a fine use of the emergency savings account, the council said via unanimous vote.

There were several requests for more information by opposing councilors. To my knowledge they went unanswered by the city administration, which is not unusual.

A year later, in May 2022, the city manager submitted a short report that was almost exclusively marketing material supplied by the company. The one with the graph omitting the Fourth of July and New Year’s Eve.

While it’s the gun detection technology that grabs headlines right now, the predictive policing software is more worrying, I (Bill) think. The pushback from the public and a few councilors only made the political will to continue throwing money at Shotspotter more apparent. The 8-3 dynamic we saw then still exists. After the issues simmered down, arrest press releases from the WPD were suddenly stuffed with credit to Shotspotter.

In the 2023 annual report on crime statistics from the police chief, there is an entire section dedicated to the benefits of Shotspotter gun detection and AI. It reads:

Our department continues to rely on crime analysis and intelligence-led policing as tools to help guide the operations of the department. The command staff of the department meets weekly to discuss emerging crime trends identified through crime analysis and community feedback. Officials then use the information to direct patrols to crime hot spots and develop focused deterrence strategies.

Hmmm, wonder where the “crime hot spots” are?

The council hasn’t met since the Wired story dropped. It’s a toss up whether it prompts a discussion. It probably won’t. If a progressive councilor forces a discussion, it won’t accomplish anything save an opportunity to vent. The eight-vote majority will spike any serious attempt to reevaluate Shotspotter, and most of them would take such a move as a personal attack. We’ve seen this show before.

We’ve not come close to generating the sort of public pressure advocates were able to pull off in Chicago. Everyone who tried back in 2021 was punished for caring. Told to kick rocks. And the energy around police reform which existed then has since withered dramatically. It would be naive to expect a new and more powerful opposition movement to emerge. And the last one didn’t even come close to succeeding.

I’d love to be proven wrong, of course! There should be a lot of public pressure on this! And even just forcing the powers that be to publicly justify their support of this patently harmful, bigoted tool is a righteous use of time and energy.

But I (Bill) take being honest seriously. And my honest assessment is I don’t see a lane here. We’re stuck with Shotspotter for the foreseeable future. What happened in Chicago just flatly will not happen here. The cops get what they want. Whether they should have it is a moot point.

What Is the point?

When there is a national reckoning over a clearly harmful and racist technology, one that our police department employs with enthusiasm while we pay for it, and you can’t reasonably expect it to even enter the local conversation, let alone lead to change… it begs a heavy question. What is the point of our local democracy? Is it even that? A democracy?

If the 8-3 dynamic on the council that keeps the Shotspotter checks signed were to one day flip to a 6-5 majority who want to stop writing them… could they? It’s an open question. And one that begs another: is local democracy a mirage? Is there really a forum for the public will to direct city hall? Or is it the opposite–a clever shield between real power and a powerless public. A forum to merely inflict punishment on those members of the public foolish enough to believe they have a say? Is it a lie that maintains the docility of the serfs? Open question.

Absent whether the public has any power, there’s a separate question: Does city hall? Do the council and the city manager have any power over the cops? In theory they do. The council oversees the city manager who oversees the police chief. That’s how it should work. But it’s worth considering the idea that it doesn’t work that way—that the power dynamic is, in a practical sense, inverted. The cops oversee the city manager who oversees the council, just with the plausible deniability factor of everyone involved pretending otherwise.

Consider that the WPD has a very long record of settling or outright losing on claims of police brutality, harassment, and racism, and a very very short record of actually addressing such issues. In the cases of an illegal interrogation, a wrongful conviction based on police lying, a multitude of physical assaults, and the murder of a mentally ill man exhibiting obvious signs of mental illness, no policies were changed, and officers involved were not disciplined. In fact, many have since been promoted. The city council is expressly prohibited by the charter from direct decision-making in the hiring or firing of a police chief. Even if we didn’t have such a cop-friendly council, there is limited authority, though that’s not an excuse to let them off the hook about what they could do. Unlike the council, the city manager has the authority to hire and fire the police chief, as well as guide their leadership. But there doesn’t seem to be any motivation to do so. When the city pays out settlements, the money (and it’s a lot of money) doesn’t come from the police’s pockets, nor the city manager’s, really. Ultimately, settlements are paid out of our pockets. We feel it through the loss of all the other services we can’t afford because we’re paying millions in judgements and settlements.

In contrast, the police have a lot of power over city leadership, in particular the council. If they don’t like how you vote or what you say about them, they can loudly oppose your candidacy through their union. They can make the district you represent feel less safe to the people most likely to vote, through their words and also their absence and inaction, since many people have never seen a non-carceral solution to antisocial behavior.

As a police and prison abolitionist, I (Chris) am keenly aware that the answer isn’t just to let anything happen and just say it’s OK: There needs to be a response of some kind. There needs to be someone you can call when someone assaults you, or when you or someone else is in a mental health crisis, or there’s a car accident. As an abolitionist, I just also believe there are better solutions than police as we know them. Abolitionism without actual solutions, however, is boring and reductive, and the beauty of abolitionist practice isn’t thinking about what you don’t want, but what you do want: I would argue that the actual prevention of “crime” is something you do by breaking cycles of neglect and abuse, and healing harmed people, and of course meeting basic needs like food, shelter, and clothing. You prevent “crime“ by stopping someone from getting to an assaultive place to begin with. You prevent “crime” with a social infrastructure that can catch people before they fall. You prevent it with community care and material support to alleviate suffering. It’s social workers, and other non-carceral systems of mental health, substance use, and community safety response. It’s public low/no-cost housing, and free food, and just straight money into the hands of people who need money. These are all things we could fund, and if you’re wondering where the money would come from, well…the cops have a whole bunch and they aren’t using it very effectively. I’d start there!

When you take a good hard look, as I (Bill) think we did in this piece, at the relationship between a company like Shotspotter and a city like Worcester, there are long threads to be pulled from a small fray. What keeps the Shotspotter contract alive here, despite a rock-solid case it should die, is a confluence of universal power dynamics. We can barely comprehend an alternative to “police as we know them,” as Chris put it. The “what would replace the police” concern is entirely academic anyway. We can’t even get them to stop using a technology that obviously doesn’t work.

The logic and morality informing the critique of this technology have no authority over a jarringly different logic and morality which brought it to being and keep it in place. With the former set of values, you’re left to shout into the void. With the latter, you align yourself with all the world’s power. Shotspotter is, in this way, the same as the AI training to take your job, the money that flows from your paycheck to a far-off genocide, the rent increase that your landlord surprises you with, the health problem you’re not getting checked, the friend you lost to an overdose, the tent you see in the woods. It’s out of your control. It doesn’t have to make sense. Yours are not the pressing concerns. “Crime” is not tethered to “safety.”

Chris Robarge (@Robarge) works for the Massachusetts Bail Fund and with me at the Rewind Video Store. He wrote one of my favorite Worcester Sucks posts ever about the destructive pattern of high speed police chases in Worcester.

School Committee Preview

The newest member of the Worcester Sucks team, Aislinn Doyle, is writing up short advances of the school committee meetings on top of her monthly WPS In Brief column (read the first one here!). The meeting advances are too short to send out to the entire list on their own, but I’ll tease them in my weekly posts. Like so:

March 4 Finance, Operations and Governance (FOG) Standing Committee Meeting

The next Finance, Operations and Governance meeting is scheduled for Monday, March 4 at 4:45pm at the Durkin Administration Building. There are three items on the agenda:

-An item about offering summer custodial jobs to students 16+.

-An item approving the school calendar for the next three years. The proposed calendar now includes Indigenous People’s Day alongside Columbus Day.

-And for a second time in FOG, an item to accept a donation from the Gene Haas Foundation. The administration is requesting it be filed. When this originally appeared on the agenda at the October general school committee meeting there was long debate around the ethics of accepting the donation due to the naming requirement.

The full agenda is here. You can watch it via Zoom or Facebook Live.

Gus Takes Over The World #2

Here’s the second edition of Katie Nowicki’s new comic strip about our cat Gus. It’s so cute I love it.

These will be a weekly feature of these Sunday posts going forward! We have our own funny pages!

Please Support Worcester Sucks!

The main piece today took a ton of effort and I don’t have it in me to do my customary odds and ends. Instead, I’ll cut right to the chase and ask again that you consider supporting this publication!

This newsletter is supported entirely by reader subscriptions. I’m able to pay contributors like Chris and Aislinn to write these posts because you pay me to run this newsletter! The more paid subscribers we get, the more we’re able to do! And we just hit 700, which I already told you but still think is very cool.

It’s just a few bucks a month, and unlike a Telegram subscription, it doesn’t go to some media conglomerate that makes money by laying people off. Rather, it goes directly to Worcester people writing about Worcester.

Ok cheers! Til next time.

Good piece 👏

When "Sound Thinking" comes up with its ShotStopping strategy and product line, ring the bell. Until then, ShotSpotter isn't doing Worcester or any city truly interested in stopping gun violence any justice at all for the millions spent or the lives lost.