Endless punishment for the crime of existing

How a city bureaucracy serves as a factory for manufacturing an underclass

Hello everyone! Coming to you early this week because me and Katie are going on a much needed vacation. We’re driving down to Key West (road trip!) and spending a few days with her folks. So you won’t be hearing from me until at least next Sunday.

Luckily, we have a lot to talk about right now! And this post is quite beefy. Lots to hold you over til the next one. Take your time with it!

Writing about Worcester the way that I do is fun and fulfilling but it is also a lot of work! This is very much a full time job. Please consider supporting Worcester Sucks with a paid subscription or a tip or a merch order. If you subscribe today, you have the added bonus of knowing I will surely spend the $5 on some sort of tiki drink this weekend. The kind with the little paper fan on the tooth pick.

The full time job is not just the newsletter however. There’s also the Worcester Community Media Foundation, which put on its first book club meeting last week! As I wrote about at length in the last post, that book club is a proof of concept for the hole WCMF can fill in local journalism. I’m also going to give a video essay for the Rewind Video Club Patreon a shot this week. If you are interested in doing local journalism video editing or production work send me a line billshaner91 at gmail. If this first attempt goes well, I see a route by which the video store could become a video production studio also.

Aaaand I also do the Worcestery Council Theatre 3000 Twitch stream every week! This week, because there was no council, we brought on a couple of real ones for great interviews focused on homelessness and the Supreme Court. First, Councilor Etel Haxhiaj, then Chris Robarge of the Mass Bail Fund and my partner in crime at Rewind Video. You can watch it here.

We did these interviews because the council is on a three week hiatus. The conversation was so nice and productive it makes me think we might be wasting our time watching city council meetings. But alas, we must.

Ok, onto the Worcester Sucks part of the work!

Table of contents (BETA test)

When these posts have a lot of different, equally important subsections, I don’t often make that super clear. I sorta just cram em all in there, and it both buries my hard work and makes for daunting reading. This is an attempt at fixing that! Let me know if you appreciate it.

The post today comes in four main sections. It’s also too long for most email providers so might be better to open it in a browser.

Section 1: “What does the city do for the nation?” An observation and a question to keep in mind when reading sections two and three.

Section 2: “What does the SCOTUS homelessness case mean for Worcester?”

Section 3: “Why are we doing this?” Equity theft via the little-known process of tax lien deed auctions.

Section 4: “The Clark situation.” On the now-infamous Wall Street Journal op-ed and all the bad-faith fracas.

Then after that the customary odds and ends.

What does the city do for the nation?

In various quiet ways—like the endless sweeps and auctioning off the homes of tax debtors—a city bureaucracy serves as a factory for manufacturing an underclass. The state dangles the promise of America while the city uses these processes to enforces the reality of it–dictates where the dream exists and where it doesn’t. The whole premise of America would crumble if the state had to explain that the dream is carefully rationed. That it isn’t actually available to everyone. Leaving the rationing to the mundane arena of city governance makes it invisible. No one has to say that the “bad neighborhoods” exist by design. No one has to say poverty is a state project. City governments don’t even have to recognize the role they play in this. In competing among each other for a perceived “niceness,” property value is the primary metric and the metric is juiced by the perception it’s a “desirable” place. This means, necessarily, eradicating what isn’t “nice.”

This equity theft practice and the city’s homelessness response both operate on a certain moral equation. Achieving a goal for “the city”–sanitized public spaces, tax revenue projections–makes ruining the lives of certain residents permissible. Keeping the unhoused stuck in a perpetual and inescapable cycle is tolerable if it means they can be banished from certain spaces. Stripping a struggling homeowner of their house is tolerable so long as the tax account is squared. Both of these processes are reliably invisible, with rare and fleeting exceptions. The people harmed are invisible.

Cities, as a collective entity, carry out the state project of maintaining poverty by trying, individually, to remove themselves from it. Seeing it that way makes the endless sweeps and the robbery of citizens with paltry tax debts make sense. Just a thought.

And, for what it’s worth, a thought you’re unlikely to read in any other local outlet!

What does the SCOTUS homelessness case mean for Worcester?

Homelessness is in the national news this week for a slightly different reason than usual! Rather than the same old “cities under siege” stories we’re used to seeing, the Sauron’s Eye of the national press corps turned its attention to the Supreme Court and the question of whether cities can directly criminalize homelessness with fines and jail time. For most cities, Worcester included, “directly” is the operative term. As we’ll get into, Worcester has done a bang up job of this criminalization without any specific law on the books.

While we won’t know for sure until June, it appears likely the Supreme Court is going to choose the ghoulish path and rule that not having a home is, in fact, a crime. SCOTUS heard oral arguments in the Grants Pass case on Monday. Put as simple as possible, the question is whether a city can punish people for sleeping outside when they have nowhere else to sleep. The Grants Pass ordinance directly fines people some $500 a pop for sleeping outside with a blanket. Is it cruel and unusual punishment, as defined by the 8th Amendment, or is it not cruel and not unusual?

The consensus takeaway is that the majority of the court appears ready to say it’s neither cruel nor unusual. I listened to the oral arguments, and while I’m no expert on the Supreme Court, it was clear to me. Only the “liberal” justices took lines of inquiry which were sympathetic to the unhoused. The conservative majority remained tightly focused on whether homelessness is a “status” or “conduct,” in a legal sense. They tossed out all manner of strange hypotheticals and analogies. “Is being a bank robber a status?” asked Chief Justice John Roberts. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked whether there’s a right to shit and piss outside.

“How about if there are no public bathroom facilities, do people have an Eighth Amendment right to defecate and urinate outdoors?” he asked.

The oral arguments made it clear most justices have only a dim understanding of homelessness, how cities respond to it, and what produces it. Justice Samuel Alito, for instance, asked a question you might sooner expect to hear on the city council floor.

“Does it matter whether the person grew up in the town or not?” he asked, for some reason.

Almost two hours in, Justice Clarence Thomas asked a question that was so baseline and stupid it was stunning: “Is there an ordinance here that says to be homeless is a crime?” Nice of you to join us, Clarence! The attorney for the unhoused plaintiff in the case was like uhhhh yeah that’s why we’re here dawg. “The language ‘for the purposes of a temporary place to live’ makes homelessness into the definition of the offense.”

I’ve never listened to a SCOTUS oral argument before, but I was expecting just a bit more from these people we’re told are god-like legal minds and who hold god-like power over the country.

If the court rules the way everyone expects them to, it won’t lead to any immediate sweeping changes in the way cities handle unhoused populations. Rather, it will open a door for cities so inclined to pursue more punitive and overt measures. Unfortunately, that’s most cities. To varying degrees, the recent surge in homeless populations has prompted increasingly cruel responses. The Supreme Court ruling will only allow cities to feel more comfortable with local ordinances that expressly criminalize homelessness.

But what’s been lost in the conversation, and what I’d like to focus on, is the fact that cities don’t need overt anti-homeless ordinances to make homelessness illegal. They get by just fine without them. The Supreme Court ruling only allows most cities to codify what they’ve already been doing for years.

Worcester, it just so happens, is a great example of such a city.

There’s no ordinance like the one in Grants Pass on the books here that directly criminalizes sleeping outside, but there doesn’t need to be. It’s made a crime by a more subtle and nuanced system of laws and policies and practices. Homeless people aren’t outright fined or jailed for being homeless, but they’re still routinely punished. The end goal of removing them from wherever they are is still accomplished.

A city like Worcester would probably see adopting a more overtly stated anti-homelessness ordinance a political liability. If they’re already able to accomplish the criminalization just fine, a new ordinance only invites unwanted public scrutiny. Bad optics. Just because they have the legal green light from the Supreme Court doesn’t mean they’d avail themselves.

Worcester’s strategy is a rather on-the-nose example of what sociologist Chris Herring calls “pervasive penality” In a 2019 sociology paper titled “Complaint-Oriented Policing: Regulating Homelessness in Public Space” (read it here, and shouts out again to Clark prof Jack Delehanty for putting it in front of me) he examines San Francisco's homelessness response to illustrate the concept. It’s remarkably similar to Worcester’s. Reading the article, I found myself forgetting it was set in another city.

“Pervasive penality” is essentially the process of criminalizing homelessness without saying so out loud. Without a direct law or ordinance on the books, the police use a combination of move-along orders, destruction of personal property, outstanding warrants, and the threat of arrest to remove homeless people from where they happen to be. As Herring describes, it’s a “a punitive process of police interactions that fall short of arrest and are pervasive in both their frequency and lingering impact.” In other words, the city doesn’t need a specific law to make homelessness illegal. They can punish and banish the unhoused just fine without one.

Without ever using the term, I’ve written a lot about what the “pervasive penality” looks like here in Worcester. Encampment sweeps are the primary tool, and they’re carried out routinely. The threat of catching a trespassing charge is enough of cudgel to make an unhoused person pack up and move. So is the threat of personal property being deemed “abandoned” and thrown in the trash. At one sweep, I witnessed the cops use the threat of running an unhoused person’s name for outstanding warrants as a coercive tool to move them along. I’ve heard from more than a few unhoused people that their belongings were confiscated and trashed at one point or another when they weren’t at their tents. Unhoused people tend to have outstanding warrants for charges related to drug possession or sex work or trespassing or disturbing the peace. The threat of being taken in is as coercive as being taken in.

Herring describes this as a “sequence of criminal justice contact that is more powerful than the sum of its parts.” He continues:

This process also diminishes citizenship by cultivating a distrust not only of the police, but of various state institutions of poverty management and the public at large. Even without overtly taking the punitive actions of arrest and incarceration, in what may appear a more compassionate approach to the problem, the failure to deal with root causes of homelessness leads city officials to develop short-term solutions that exacerbate the problems faced by the unhoused and fail to stop the seemingly endless flow of complaints.

In one paragraph, a summary of all my writing on the unhoused here in Worcester! Failing to deal with root causes while advertising the punitive response as a “more compassionate approach.” The endless flow of complaints leads to an endless cycle of harassment and coercion.

In San Francisco as in Worcester, the police operate on a complaint-based model. If they get a complaint about a homeless person, they’re duty-bound to respond. The complaints can come from the public or from city hall or from private businesses or wherever else. They must be responded to regardless.

For instance the high profile sweep of the Walmart encampment in 2021 was initiated, in part, by a complaint lodged by Walmart.

The similarly high profile sweep of the encampment outside the RMV temporary shelter was initiated by a complaint lodged by the organization running the shelter.

Smaller encampment sweeps happen all the time and never get any press attention. We never know what complaint initiates it or whether the complaint is reasonable. Anyone can call the cops on the unhoused for any reason and the cops have to respond in some way. There doesn’t have to be a clear crime. It all falls under the blanket of “quality of life issue.”

In San Francisco, Herring notes, the cops developed a new term for complaints about the unhoused which didn’t point to a specific crime. They’re simply called “homeless concern” and they still have to clear out the complaint.

Herring’s piece includes dispatches from several ride-alongs with the San Fran beat cops responding to these complaints. He found, unsurprisingly, that the cops themselves don’t think they’re helping. He quotes one officer:

I can take a guy to shelter, but it’s only going to be for one night and then they’re going to be back out on the street. Some of these people are crazy or addicted, and that’s like a disease. Who are we kidding in thinking they’ll do well sleeping bunked with 200 other guys. . . . Policing these folks doesn’t do anything to get them off the streets. If anything, it keeps them there longer.

They have to respond to complaints, but they don’t want to. In fact they often resent the complaints that come in. Herring quotes another officer:

I mean, I’m trying to get through this queue [of homeless complaints] and it’s like just because the supervisor’s friend or supporter has an issue, or some camp near the highway turnoff in his district makes him look like he’s not dealing with homelessness we got to deal with it.

They do as little as possible to clear the complaint, then move on. San Fran cops told Herring they don’t think they should be the ones doing the job. That it should be social workers on these calls, and that it’s not real police work. This is, mind you, exactly in line with the central critique of Defund The Police. But alas, what’s the point of making that point?

If I had the same access to WPD officers doing the same work, I’m sure I’d find the same sort of sentiment. The WPD would never give a reporter that kind of access, though. The narrative around “compassionate response” wouldn’t survive such a glimpse at the real thing.

Instead, the city is able to effectively carry out a strategy of pervasive penality while telling the public they’re trying their best to solve a difficult issue. They get to say they try to “connect people to services” without having to say whether the services exist. They get to call it a “quality of life issue” without having to say whose life merits quality and whose doesn’t. They can effectively banish people to the least visible corners of the city and keep them from getting too comfortable there.

And that brings us to the—cue ominous music—Business Improvement Districts.

Worcester has one of these in the downtown, though you don’t often hear about it. When you do, you’re most likely to hear it described as a “beautification” effort. Essentially, it’s a private contractor paid for by businesses within the district that supplies “community ambassadors.” These folks pick up garbage and change trash cans and such, but they also serve as private security. Herring details how that works in San Francisco, and it’s safe to say that’s how it works here too.

During my time recycling, panhandling, or simply hanging out with houseless companions in these districts, we would be stopped regularly by BID security and sanitation staff, officially called “community ambassadors,” and told to leave the area or else the police would be called.

These “community ambassadors” don’t have the power to arrest or fine people, but just being able to say to an unhoused person they’ll call the cops if they don’t move along is enough to get most people to move along. The ambassadors are able to enforce the de facto crime of existing somewhere while unhoused without even being police officers. Herring also details how that interaction works.

During my ride-alongs with officers, I observed several community ambassadors and security guards who were on a first-name basis with officers. On my first ride-along with officers, we arrived at the entrance to the Civic Center Auditorium to evict an encampment, and before we even got out of the vehicle, a community ambassador walked up to the car window to tell us, “it’s always the best time of the day seeing you guys roll up.”

There’s reporting work to be done outside the scope of this article to try to get some documentation of the way Worcester’s “community ambassadors” interact with the police. But, for now, it’s enough to say that we have the exact same model as the one Herring details in San Fran.

We also have a 311 app, which in San Fran has served to be an effective anti-homeless tool for the city. The unhoused people Herring was embedded with called 311 the “snitch app” based on the way people would use it to direct the cops to the presence of homeless people. As we’re famously behind the times here in Worcester;our 311 app is only a year or so old. But San Fran has had it for a while, and Herring was able to use data to show that 311 increased the amount of homeless complaints—and thus police enforcement—dramatically.

...unsheltered homelessness increased by less than 1 percent between 2013 and 2017, yet 911 dispatches for homeless complaints increased 72 percent and 311 complaints increased 781 percent.

The data visualization is stunning.

Worcester’s 311 app has a public complaint log and I scrolled back through it to the beginning, last August. Most of the complaints are about trash and potholes, but there were three examples worth looking at here.

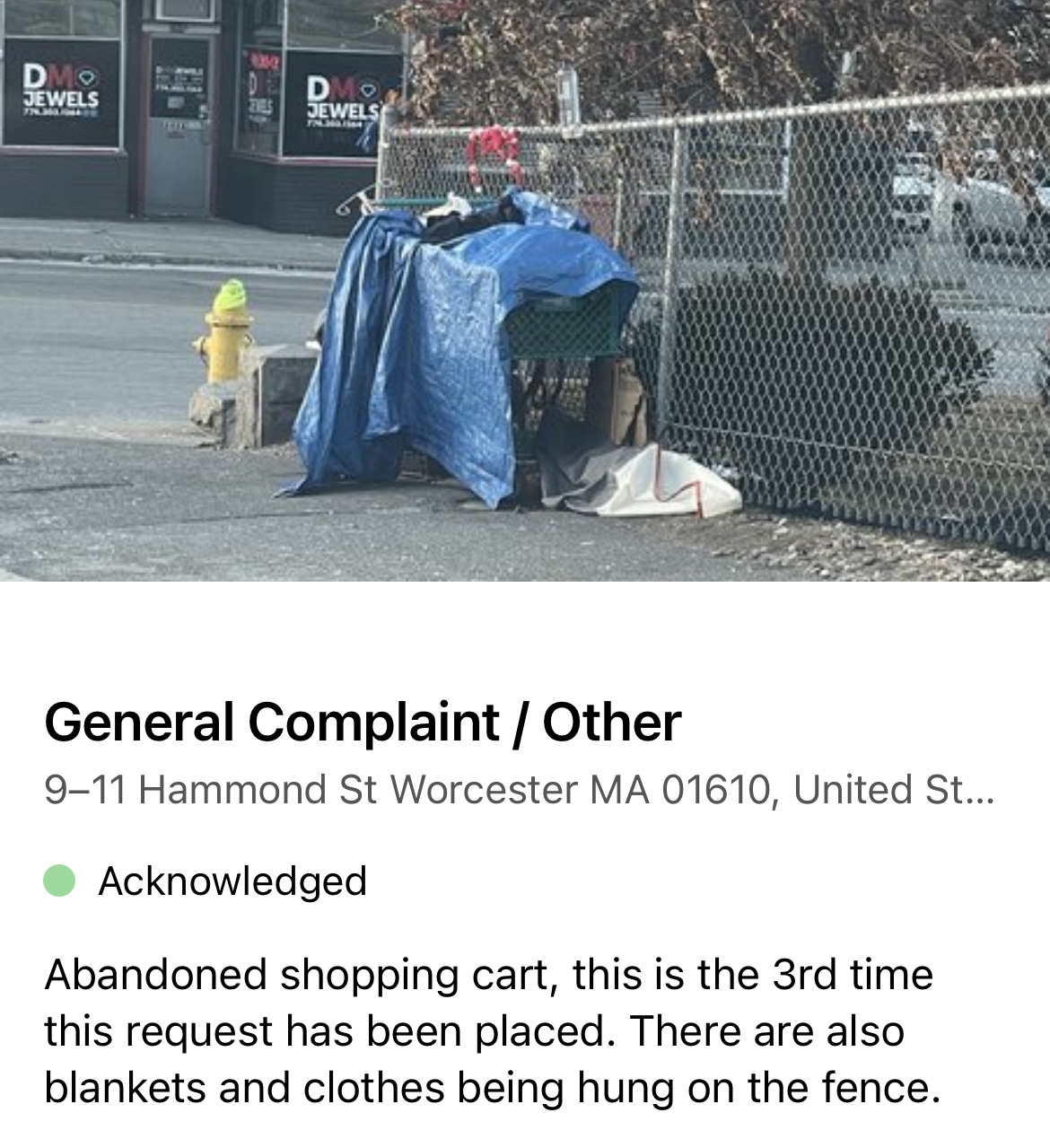

Exhibit A:

Is it abandoned, or do you just want it thrown away?

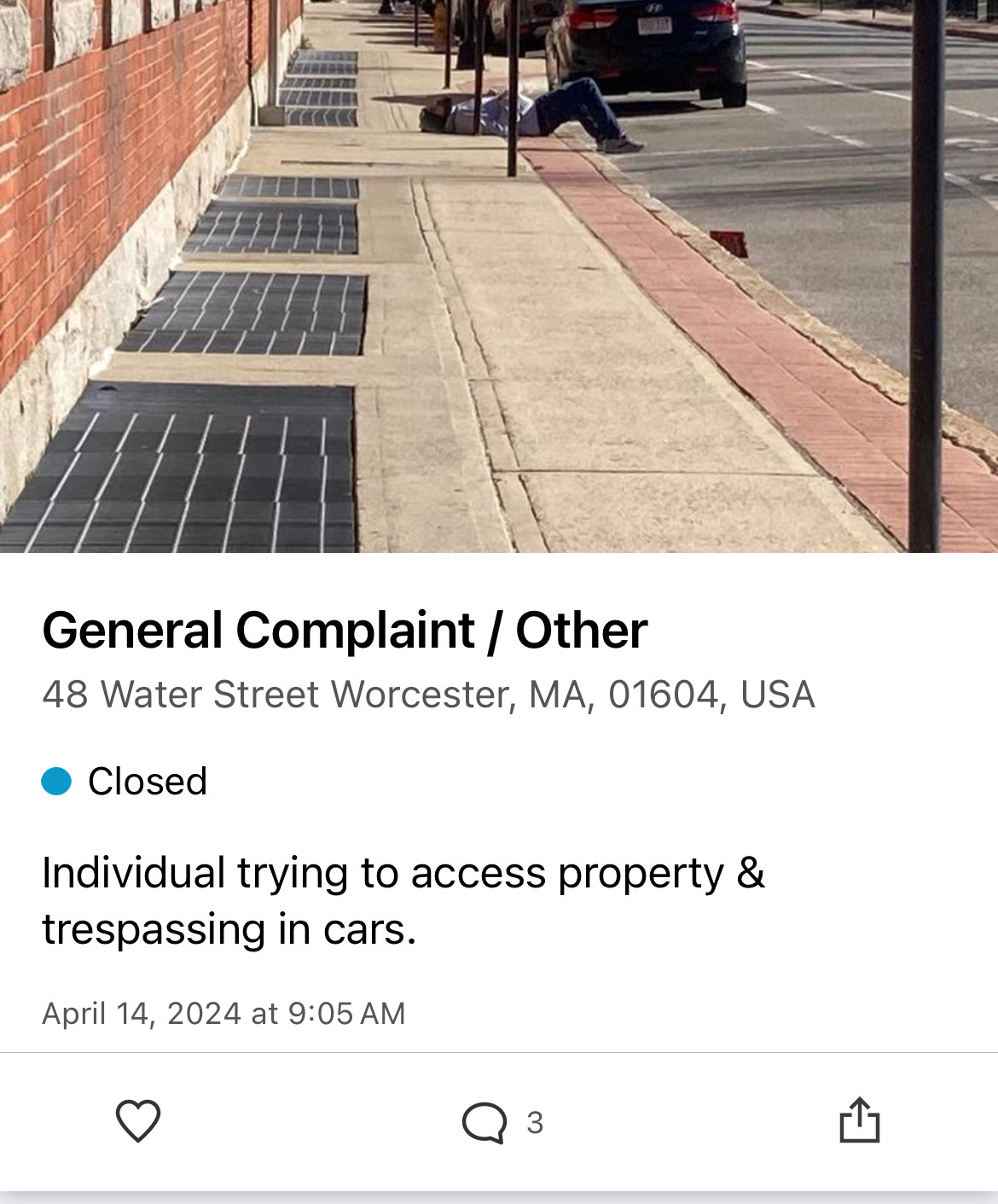

Exhibit B:

That individual appears to be lying on the sidewalk, not “trespassing in cars,” whatever that means. The way the complaint is worded raises suspicion this man was doing anything but lying down. Nevertheless, in the comments, the city directed the person to call WPD, then reported the complaint had been resolved, without saying what “resolved” means.

Then there’s Exhibit C, which is the most on-the-nose.

Notice how all of these fall into the “General Complaint / Other” category. When you go to fill out a complaint on the app, there’s categories for broken street lights and abandoned cars and potholes, but none for “homeless person.” It appears the “General Complaint” category will function as the stand-in term.

So, to recap, the complaint-based model of our police department’s homelessness response, the use of and threat of a trespassing charge, outstanding warrants, the policy of routine encampment evictions, the “community ambassadors” and exclusions zone they create, as well as the 311 app all work together to do what an anti-homeless ordinance like the one in Grants Pass would do. They don’t need to fine people for sleeping outside directly to effectively punish them.

Even if the Supreme Court surprises everyone and rules the other way on Grants Pass, it wouldn’t put a stop to this pervasive penality. At best, it might make it a bit more complicated. It would be trickier to do the endless sweeps, for instance. But they’d find a way, I’m sure. After all, they don’t need to arrest or fine people to make them move.

But the safe money is on the Supreme Court ruling in favor of a city’s constitutional right to make homelessness a crime. In cities like Worcester it’s already a crime. The decision will merely be a blessing from on high to stay the course. The endless complaints of “homeless concern” will trigger endless responses. The people experiencing homelessness will continue to receive endless punishment for the crime of existing.

Why are we doing this?

I guess this is the legal edition of Worcester Sucks because there’s another highly relevant court decision in the news. A Massachusetts judge ruled last week that cities and towns can no longer partake in the quiet and insidious practice of “equity theft.” It goes without saying Worcester partakes in this and so much so that it’s facing at least one lawsuit for it. And, as we’ll get to, the court ruling doesn’t mean it’ll end.

“Equity theft” is what can happen to you in Worcester when you fall behind on your property taxes. By a quirk in state law, cities are allowed to auction off the whole ass deed of a property if the property owner falls behind on taxes. At the auction, a third party “buys” the debt, settles the account with the city, then walk away with the whole house. For property owners, some $3,000 in outstanding taxes can result in the loss of a $300,000 home.

Just recently, the city was hit with a lawsuit after auctioning off the home of a woman who owed $2,600 in taxes. The city sold the $300,000 home to a buyer with some vague LLC, who then evicted the previous owner. The city ruined this woman’s life in order to collect a few thousand dollars.

It’s surreal that this is a thing that happens at all. And in Worcester it happens a lot. Since 2018, the city has sold off some 400 properties in this way. The buyer in the above example, Tallage Brooks LLC, has taken dozens of homes from Worcester residents via this auction system. This Week In Worcester dug up a study that showed that between 2014 and 2020, the company made $1.5 million in profit off 21 properties. There’s a whole cottage industry.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that this practice was unconstitutional. The recent ruling in Massachusetts is the first time a state judge has acted on that ruling. Hampden Superior Court Judge Michael Callan cited the SCOTUS decision in barring Springfield from auctioning the equity of a home.

Massachusetts law doesn’t so much permit this equity seizure so much as it fails to address it. Left with no reason not to, cities like Worcester take people’s homes and sell them off. It’s a choice!

The Hampden Superior Court ruling doesn’t put an end to the practice, however. The state Supreme Judicial Court would have to take it up, or the state legislature would have to pass a law. Neither institution is necessarily obligated to do so, and so it remains an open question whether cities will keep being allowed to steal homes from its residents.

But it’s important to remember that this practice is a choice. Worcester could stop doing this transparently evil thing tomorrow if it so chooses. They could have stopped after the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional! But they didn’t. In fact, city hall doubled down after that ruling. According to This Week In Worcester, the city held an auction for some 200 properties just 13 days after the SCOTUS ruling. On the list was a property which owed $33.47 in taxes. Imagine losing your home over 30 bucks?

City hall shouldn’t have to be forced by law to put an end to this practice. It should be a source of great shame that it’s gone on as long as it has.

The Clark situation

Clark students have released an open letter with some 541 signatures blasting the administration and former professor Mary Jane Rein over the whole Wall Street Journal op-ed thing. I’ve avoided paying much attention to this op-ed for sanity reasons and can’t bring myself to lay out the background. This WGBH writeup does a good job.

Rein’s “Why I’m Leaving Clark University” op-ed is rage bait in line with a national trend of rage bait over “campus intolerance.” It’s a fake controversy and the people advancing it tend to find themselves on the winning end of a cash grab. I’d imagine for instance that Rein is making a bit more money at Assumption now, heading up the new “Center For Civic Friendship.” The open letter adds some missing reality to the situation. It’s strange that none of the details in this passage, for instance, have made it into the wider coverage.

To start, we want to highlight a few key details that were left out about the specific event referenced. First, the event was held at Worcester State University, where an Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldier was invited to speak on their experience. The organizers of the event and the speaker used incendiary, dehumanizing, racist, Islamophobic, and language inciting genocide. For example, the speaker called all civilians of Gaza “human shields,” and that “[Israel] is the last line of defense for Western civilization”. Given the incendiary language, audience members responded in protest. Several Worcester State police removed audience members for their disruptions in response to the provocations by the language used by the organizers and the speaker.

The thing that makes me soooo tired about this story is that Rein’s job was the executive director of a center for “genocide studies.” If you can’t take a couple kids shouting about an ongoing genocide, perhaps genocide studies is not for you?

It’s hard not to see these stories, especially the Columbia one but this Clark one too, taken together, as a concerted effort to turn the lens away from an ongoing world historic atrocity.

But I’ll leave it at that for now.

Odds and ends

Ahhhh the end of the post. If you made it this far, you must like what you’re reading or really hate it. Either way, consider tossing me and the rest of the team a few bones!

Speaking of the rest of the team, did you know Worcester Sucks schools correspondent Aislinn Doyle does school committee previews? Check out this week’s preview and toggle the notifications on in your Worcester Sucks account to get these previews in your inbox.

I had the pleasure of going on The Weed Out, a podcast run by some righteous folks out in Western Mass. It was a great talk. Here’s the YouTube version and then more ways to listen on their website.

Here are some stray links of note:

The WRTA is fare free through 2025!

The state has set a December deadline set for Holden to comply with the zoning change that has them kicking and screaming.

Very related: Worcester has the third worst rental market in the country it turns out.

Third worst rental market in the us baby

Some good/interesting news: First Worcester Miyawaki Forest Planting Will Green Barren Library Parking Lot

Bad landlords to blame for a new downtown restaurant’s failure to open.

Aaand a piece of single source reporting on the police as protagonists courtesy the Telegram, interesting for those who enjoyed the “Crime Gun Intelligence” section at the top of my last post.

Ok have a good week everyone! Vacation time for me.

Good piece 👏