Well well well what do we have here another Worcester Sucks post in your inbox/internet browser! Third this week depending on if you count Sunday as the last day of the week or the first day of the week. I myself am unsure but also unbothered.

Today’s piece is a deep historical dive into the Worcester of another time, and comes courtesy of Tyler Wolanin, a local political history buff who really knows this stuff and put the work in.

I like this essay a lot. It’s well-researched and offers a lot of comparison points to the modern day. Thought it best to put it up on a Sunday morning—the time traditionally reserved for the sort of deep-dive journalism that makes you think about your world more than inform you of it. In past newsrooms these sorts of “Sunday stories” were at once coveted and dreaded assignments. They take a lot of work! But that’s what makes them good. Please sign up for a paid subscription so I can pay writers like Tyler for work like this! It makes us all better. But I can only pay writers if I have subscribers paying me, you feel? I’m sort of just a middleman in that way. Anyway, it’s just 1.5 Dunkies a month.

Or send a tip my way! (Venmo / Paypal)

Tyler’s story is well-suited for this Sunday in particular, with the preliminary election in the rear view and the general election on the horizon. These next two months are bound to be a little chaotic. After the poor showing in the preliminary election from our local right wingers, I’d expect they’ll amp up the hysteria big time.

In case you missed it, I put up a thorough recap of the election results on Thursday, examining how and why it was such an encouraging night.

Then in case that’s not enough for you, me and the Stream Boys brought on local reporter extraordinaire Neal McMamara to talk about the results even more. Check it out: Worcester Sucks Power Hour Ep. 6 ft Neal McNamara. And make sure you’re subscribed to the Wootenanny Twitch channel to catch these Power Hour recordings live. (Phew. I’ve been a busy boy lately. Check the “odds and ends” section at the end for some more cool updates on Rewind Video Store and other stuff!)

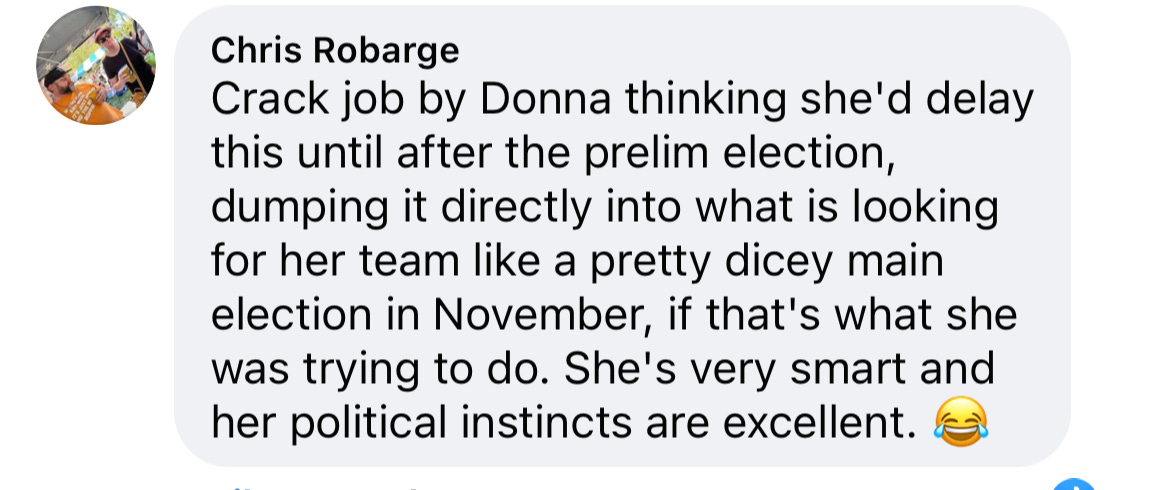

One thing that’s sure to bring out some hysterics is the crisis pregnancy center ordinance issue coming to a head on Tuesday. (Item 19I, as well as 19A-D on the agenda). If you’ll remember, Councilor Donna Colorio “held” the CPC orders at the last council meeting, pushing them from a Preliminary Election issue to a General Election issue. A political genius at work, as Robarge points out here:

But let’s get to the main event. More than anything, Tyler’s piece today is about How We’ve Always Been Like This, I think. But it is also a very strong endorsement for changing our current Plan E political system. Local politics seemed to have mattered just a bit more in the 1930s, before we moved over to a “weak mayor” system. Worth thinking about why. I have more thoughts on that I’ll share below Tyler’s piece.

Take it away, Tyler!

“Face Towards Boston and Then Say ‘No! No!”: Worcester’s Raucous Mayoral Elections in the 1930s

By Tyler Wolanin

Worcester mayoral elections, where nonpartisan candidates run for mayor and city council at-large and the winner doesn’t need a majority, can get a little ideologically murky. Before the Plan E system was approved by referendum in 1947, candidates did in fact run in partisan Democratic and Republican primaries, many of which were contentious and closely fought. The campaigns of the mid-1930s are an especially useful example: they saw a governor’s meddling, an upset primary win, a new Republican mayor, a death, a special election, and another upset win.

First, a whirlwind of background (sorry): in the late 19th century, citywide elections were often won by a Citizens Coalition, an alliance between pro-development Republicans and their Irish-Catholic allies in the Democratic Party. Though the city was Republican, the party tended to nominate middle class tax-cutters whose policies were not acceptable to the city’s elite. Around the turn of the century, with an influx of new Swedish and French voters and after some local culture wars flared up over alcohol prohibition and religious schools, the Republicans were able to wrest back control from the Citizens Coalition while solidifying their party behind a pro-development agenda. An increasing number of their voters wanted new streetcars and schools for an expanding city. On a few occasions, the Irish-led Democrats were able to cobble together enough votes to elect a mayor (most dramatically with a tied vote and a new election in 1900), but these victories were fleeting and usually the result of Republican disunity.

At one point in the nineteen-aughts, the Republican base nominated a demagogic tax-cutter for mayor, and the Irish Democrats seized another victory. Rebuking the middle-class tax-cutter allies for blowing it, the growth machine of manufacturers and businessmen was able to consolidate their hold on the Republican Party. Under Pehr Holmes, candidate of the Swedish faction, the Republicans saw the growing and bustling city through World War One. After the war, though, their free-spending civic boosterism was out of step amidst an economic slowdown, ethnic strife spurred by new immigration restrictions, and nationwide prohibition that many blamed the Republicans for. The Democrats managed to elect Peter F. Sullivan, “Peter the Great,” in 1919, on a platform of decreasing spending.

Peter the Great, who had gained prominence running a steamship ticket agency that arranged for remittances to Ireland, was a natural politician. Like his Democratic predecessors, he reduced taxes and expenditures, attacking the builders and civic improvers as “men who make their pile out of the labor of children” and wanted to spend the taxpayers’ money. He was overwhelmingly reelected three times. He stayed in power by winning over unions and the French and Italian vote. After four years, though, the nation was bustling and spending again, and Peter the Great was the one who seemed out of touch with the times. The old Yankee establishment, sensing an opportunity, jumped at the chance to run Michael J. O’Hara, a rare Irish Republican, in the 1923 election. Peeling a few Irish supporters off the Democrats, and aided by a third-party candidate splitting the vote, O’Hara won narrowly.

The Republican establishment had found their man, and O’Hara’s team set to work registering enough Irish voters as Republicans to keep him in power. The Swedish felt that they had been abandoned. Without an outlet for power, members of the community turned increasingly to the Ku Klux Klan in the mid- ‘20s, but that is a different story entirely. Electorally, the Swedes backed O’Hara’s opponents in each Republican primary: first, Senator Christian Nelson in 1923 and 1925, himself a Dane; then, the leading Swedish Republican Roland S. D. Frodigh, president of the Board of Aldermen (the upper chamber of the two-level city council). Frodigh ran in 1927 with vague enough policy criticism that everyone saw through to the ethnic grievance politics underneath; he lost narrowly. He ran again in 1929, after O’Hara had crossed party lines to endorse Al Smith for President and the city had seen a Republican campaign march through a Democratic neighborhood degenerate into a massive riot. O’Hara, with his battle-hardened machine, elite support, and record as one of the city’s greatest builders, barely skated in both the primary and the general with his small but crucial bump of Irish support. “Why have 3,500 enrolled Democrats changed their enrollments or cancelled them in the last two years?” Frodigh asked, finding a conspiracy in O’Hara’s Republican voter registration efforts. O'Hara's Irish supporters, in return, suspected Frodigh of involvement in the Klan.

The Depression finally finished O’Hara off, as the suffering city finally turned on its longtime mayor who had walked the tightrope between Republican factions. Frodigh won the Republican primary in 1931, only to lose the general to Democratic nominee John C. Mahoney, an Irishman who, in the phrasing of Charles W. Estus and John F. McClymer, historians of Worcester’s Swedes, “at least… had the good grace to be a Democrat.”

Mahoney, who had also been the Democratic nominee in 1927 and 1929, was an immigrant with a thick Irish brogue who had worked his way up from shoveling coal. His catchphrase was to say that “me hands are tied and me arse is against the wall.” Making much use of New Deal job programs, Mahoney was re-elected in 1933 after a primary challenge from state representative Edward J. Kelley, based heavily on personal attacks and insinuations of corruption. Kelley, who had spent almost a dozen years in the legislature (and was on the city council before that, elected before he was even old enough to vote), gained a powerful ally for his widely anticipated rematch in 1935: James M. Curley, the Rascal King himself, had been elected Governor, and Kelley was his party floor leader in the state legislature.

Curley had spent three separate terms as mayor of Boston and was known for his crooked, and some said despotic, regime. As governor, Curley had managed to pass legislation creating and funding social programs and consolidated his own power despite a slim Republican majority in the state House of Representatives. Kelly, as floor leader, acted as one of Curley’s legislative lieutenants. Mahoney, meanwhile, had endorsed Curley’s opponent, General Charles H. Cole, in the 1934 Democratic primary. Whatever combination of revenge and power Curley sought, he set his sights on the mayoral race in Worcester.

“I have known Eddie Kelley for 11 years,” Curley told the crowd at Kelley’s very early campaign kickoff, “and I can say today he is the undisputed leader of the House in wisdom and affection.” Mahoney campaigned on his record of having “guided Worcester through the most serious economic period in its history,” and having put thousands back to work implementing New Deal programs. He had reduced tax rates in 1933 and 1934; and blamed Republicans on the city council for their increase in 1935. His hands were tied.

Before September was out, Curley’s efforts for Kelley were obvious: one state appointee managing employment for highway projects would give preference to Kelley supporters; another, a DPU trucking inspector, was expected to leverage the threat of inspection to keep trucking interests in line for Curley and Kelley. Curley’s forces also erected a massive Kelley billboard in the center of the city, courtesy of the advertising company owned by Curley’s son-in-law. Despite these efforts, Mahoney was expected to win easily. “The usually keen Mr. Curley has been gravely misled as to the real situation in the city,” journalist James H. Guilfoyle wrote in the Worcester Evening Gazette, “but he is going ahead to help Kelley in his vigorous way. He has disregarded the fact of the defeat of Kelley, which now appears certain, will be a blow to the Curley prestige.”

On primary day, October 8th, the full might of the Curley organization moved into Worcester. A fleet of out-of-town cars circulated, and a specially-wired parking lot dispatch center sent them to give rides to the polls. Curley’s efforts paid off in an upset victory, as Kelley decisively defeated Mahoney in the Democratic primary by over 3,000 votes. The mayor had struggled as any incumbent would with a difficult economy; pundits said that those who were unable to obtain jobs under the ERA (a New Deal jobs program), or those who had worked only briefly under it, blamed the mayor for not doing more. Maybe, the newspapers wrote, if the new spate of programs had started a few weeks earlier than they did, the result would have been different. Kelley, who had started his campaign months before Mahoney and who focused less on personal attacks and more on issues than he had two years prior, was the beneficiary of this anti-incumbent sentiment. Final victory was credited, though, to Curley’s assistance. One “man prominent in public life” told the defeated mayor that “you can’t beat jobs and money.” Kelley campaign workers were paid in advance, unusual for the time.

Kelley advanced to the general election. The Republicans had nominated a balanced ticket, including a Swedish woman for the at-large school committee seat; their mayoral nominee was long-serving school committee member and alderman Walter J. Cookson, a stove manufacturer by trade. By contrast, some elements of the Democratic coalition were less than satisfied with the primary outcome: the Italians had been voting Democratic since the Red Scare and immigration restriction years of the early ‘20s, but none of their council candidates had won their primaries, nor had any Lithuanian candidates. Devoid of recognition, these factions might sit out the election. The Kelley faction also worried about Mahoney supporter defections, though the mayor himself campaigned for Kelley. Still trying to avoid personal attacks, the Kelley campaign dropped African American councilor Charles E. Scott from the speaking roster after Scott criticized Cookson at a nonpartisan event (giving the Republican a chance to play indignant). Scott, a long-serving officeholder, picked up his well-loved soapbox and continued his campaign solo, leaving Kelley out of his speeches.

The Republicans puffed up their resumes and threw some punches at the current administration, but Curley was their real issue. It was an issue, the Evening Gazette said,

[T]he like of which they have never had to face before. It is so important an issue that necessarily it must cut across party lines. That issue is between the kind of government which Worcester has had up to now… the other is the Curley-Boston kind of government, so conspicuous in the State house during the past nine months that it needs no description.

And there is a subsidiary issue; perhaps some may consider it the main issue. In view of the Boston help which Mr. Kelley profited from in his campaign, it is apparent that his Boston friends, for reasons of their own, wish to dictate the kind of government which Worcester is to have henceforth. If Worcester people stand for that, we must confess that we don’t know our own city.

Cookson asked voters if they “want a sound business administration, or a political administration run by remote control.” “When you go to the voting booth,” he told his supporters, “face toward Boston and then say, ‘No! No!’ and mark your ballot for the Republican candidates. You will be happy in doing so and you won’t have to apologize for them.” After a frantic get-out-the-vote operation and an orderly election day, the voters did not, indeed, have to apologize: Cookson beat Kelley by about 2,000 votes. Kelley had won just a few hundred votes fewer than Mahoney had in 1933, but Cookson received over 9,000 votes more than the Republican candidate, Henry O. Tilton, had two years prior. Guilfoyle wrote that the Republicans were united as they had not been in years; they won with the Swedes and pushed hard for French voters, while the Democrats underperformed in Italian precincts, as they had feared. Curley, as the state and local media saw it, had been rebuked; the city, which had voted for him in the 1934 primary and general, did not vote for him in any of his subsequent statewide campaigns.

Cookson was stricken with a heart attack just four days into his term as mayor, falling into John Mahoney’s arms while laying the cornerstone of the new city hospital. He worked from his home for 10 weeks while recovering, eventually working his way back to the mayor’s office full time. In his first months as mayor, Cookson passed a budget keeping the tax rate level and undertook a reorganization of the police department. His profile was rising in the Republican Party: he traveled to the Republican National Convention in Cleveland to confer with party leaders about campaigning in New England that year. It was at the convention that he had a second heart attack while at a tumultuous reception for former president Herbert Hoover. He died on the morning of June 11, 1936, just six months into his term. William A. Bennett, president of the Board of Aldermen, also a Republican, became acting mayor.

A special election was arranged for October 6th, with a primary two weeks prior. Both parties pondered a return to familiar, tested officeholders in the September primaries. Michael J. O’Hara came out of retirement to pitch himself as an interim mayor, pledging not to run for a subsequent term. “There are no strings to my candidacy,” he said in his announcement. “The voters of Worcester resent, and rightfully so, interference from the outside, whether it be from the Governor of the Commonwealth, as they so ably demonstrated in the city election last Fall… I enter [the race] with the pledge to give the city that type of Republican administration which is needed to carry it along to further sound, businesslike development, economically but progressively.” The Democrats, meanwhile, faced the return of John Mahoney, who had “come to this decision at the request of numerous leaders within our party who feel that my candidacy will insure the return of the Democratic party to power in our city.” A rematch from the 1931 mayoral election was thus a distinct possibility.

Instead, both former mayors fell to state legislators in the primary. O’Hara was defeated by Swedish faction candidate Representative Axel U. Sternlof, who had said during the primary that the Republicans could not afford a repeat of the years when “shyster Republicans” changed their party registration from Democratic to help a “certain candidate” win. An industrial chemist, Sternlof had served in both chambers of the city council and been elected to the House of Representatives in a special election the previous year. Mahoney, meanwhile, was defeated by state senator John S. Sullivan. The defeated in both parties pledged their support to the victor; the greater turnout in the Republican primary seemed to bode well for Sternlof.

Aiming for a repeat performance, Sternlof attempted to tie his opponent to Curley. He cited a lawsuit filed at the beginning of October, less than a week before the special election, alleging that Sullivan had told a war veteran that a civil service job was created by Curley for Sullivan’s son in exchange for Sullivan’s work in the state senate on a bond issue. “He is part and parcel of the Curley regime just as much as was the Democratic nominee for mayor last year,” claimed Sternlof. In the end, however, Sullivan was victorious, narrowly beating Sternlof by about 1,000 votes. Safe Republican wards, including those of Sternlof’s Swedish base, did not turn out as heavily as expected, with defections to the Democrat, or “cutting” of the Republican in the day’s parlance. Democratic strongholds, on the other hand, were well-organized and came out heavily for Sullivan. Mahoney’s supporters did not “cut” Sullivan as they had been expected to. A recount only netted Sternlof a couple of hundred additional votes.

In the regularly scheduled election a year later, the Republicans ran former interim mayor Bennett, while Sullivan dispatched frequent candidate Harold Donahue with the help of the former Mahoney machine. With an enthusiastic Republican turnout, the election went down to a recount, where Sullivan’s attorneys issued widely panned claims of tampering. Bennett was eventually declared the winner by 96 votes; Sullivan pursued the issue through recounts and court orders, and eventually had to be forced out of office by the police after Bennett’s win was allowed to be certified. This obstinance did not endear Sullivan to the electorate, and when he was nominated again in 1939, Bennett picked up a fair number of Democratic votes on his way to a decisive win. Bennett won twice more in 1941 and 1943, racking up a high margin each time as he saw the city through World War Two; the tumultuous elections of the 1930s are thus sandwiched between eight years on each side of Republican mayors: O’Hara before and Bennett after.

The city became more Democratic after the war: Bennett escaped to the position of Worcester County sheriff as his Democratic opponent in his latter two mayoral elections, Charles F. “Jeff” Sullivan, was elected in 1945 and 1947, Worcester’s last two partisan mayoral elections. Amidst concerns of municipal corruption, Republicans and reformers passed a new charter in 1947, implementing a Plan E government. Initially, this meant a powerful city manager and a nonpartisan mayor appointed by the city council, which was elected through a ranked-choice voting system. Later changes did away with ranked-choice voting and created a popularly elected nonpartisan mayor. It is tough to imagine an election as raucous as those of the ‘30s for a position that is eclipsed in power by an unelected city manager, but 2023 may be the year if any is.

~/~

Tyler Wolanin (@tylerwolanin) is a legislative researcher from Barre. He works for the Congressional Research Service, and is obligated to tell you that the views expressed in this article are his and do not reflect the opinions or views of CRS. More New England history posts can be found on his website, and his first book, Solon in Sandals: The Political Life of Reverend Roland D. Sawyer, a biography of a western Massachusetts state legislator in the ‘20s and ‘30s, will be out next year via Lexington Books.

Other than the direct links, this article is sourced from archives of the Worcester Evening Gazette at GenealogyBank.com, the Curley scrapbooks in the College of the Holy Cross’s Archives and Special Collections, gå till Amerika by Charles W. Estus and John F. McClymer, Inventing Irish America: Generation, Class, and Ethnic Identity in a New England City, 1880-1928 by Timothy J. Meagher, “Party Splits, Not Progressives: The Origins of Proportional Representation in American Local Government” by Jack Santucci (American Politics Research 45 (3), 2017), The Reign of James the First: A Historical Record of the Administration of James M. Curley as Governor of Massachusetts by Wendell D. Howie, and The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley (1874-1958), by Jack Beatty.

Odds and Ends

Bill again! Like I said earlier, paid subscriptions are the only way I’m able to get this sort of work out into the world! If you’re a paid subscriber, you’re also getting this stuff out into the world! In other words: hey! you’re part of it.

Or send a tip my way! (Venmo / Paypal)

Reading through Tyler’s piece again, it strikes me there’s a natural follow-up story to be written here about why and how the city moved to Plan E. (Tyler, if you’re reading this, go for it!)

Several moments from the piece also resonated heavy with me as I just finished reading “Eight Hours For What We Will” an examination of working class leisure time from 1870-1920ish by Roy Rosenzweig.

This line from Tyler’s piece especially...

Peter the Great, who had gained prominence running a steamship ticket agency that arranged for remittances to Ireland, was a natural politician. Like his Democratic predecessors, he reduced taxes and expenditures, attacking the builders and civic improvers as “men who make their pile out of the labor of children” and wanted to spend the taxpayer’s money.

...had me thinking about the way Rosenzweig characterized the city’s power elite, and how eerily similar it read to the way I tend to think about the modern power elite.

In part, the mergers of the early twentieth century formalized a complex web of informal connections that had knit together the city’s industrial elite throughout the late nineteenth century. Business ties were one powerful bond uniting different parts of industrial Worcester. Wyman and Gordon, for example, initially found its major customers within Worcester — forging parts for Crompton and Knowles looms and producing copper rail bonds for Washburn and Moen. Supporting and reinforcing these business connections as well as a network of interlocking corporate and bank directorates were extensive social and cultural ties. Worcester industrialists worshipped at the same Protestant churches, belonged to the same clubs, attended the same schools, lived in the same West Side neighborhoods, vacationed at the same resorts, and married into each other’s families. (P. 14)

The more things change, am I right? I mean, just look at the continued existence of The Worcester Club, (founded in 1888!). The only difference is those guys back then actually built stuff, and now they just give tax breaks.

Some more stuff:

The Dirty Gerund folks are up to no good! They’re trying to make a movie and they’ve launched a kickstarter. Check it out. I did the $100 pledge which requires them to write a poem about me and put it online lol. Will share on here when that happens. Malt Schlitzmann, a ring leader of sorts for the Dirty Gerund, wrote quite possibly the most unhinged post on this website back last April: “An Insane Person For An Insane Job.” Excited for whatever insane thing this movie project becomes!

This tweet seems to have struck a nerve lol

Perhaps because it is true?

And hey look at this! Rewind Video Store has a sign!

That’s Brian Denahy right there. He volunteered his time and talent Friday afternoon and he did an amazing job. The thing is hand painted! Make sure you’re following him on Instagram and hitting him up for all your sign painting needs! Also thank you to Travis Duda (@hunchbacktravis) for the logo design! Make sure you are also hitting him up for all your design needs.

One more plug: Come out to Redemption Rock Brewery next Sunday, Sept. 17, 5-8 p.m. for a benefit event for Katie. It’s called Bills for Bosoms and it’s gonna be a fun time!

Ok that’s all folks! More soon!