Hey all, really special episode here. The other day, I had Heather Prunier, Tom Marino and Lynn Kee over my apartment for a catch-up conversation on a major breakthrough in Heather’s fight for accountability. She finally received some of the records in the investigatory file.

Yesterday, over on This Week In Worcester, Tom Marino published a substantive, detailed report on the contents of this cache of never-before-seen records. Would highly suggest reading that before listening, as we spend most of the time discussing the 23-page packet—what’s in it and perhaps more importantly, what isn’t.

We talk about Heather’s fight for these records, what’s at stake, what gets to be “political” and what doesn’t. (Unfortunately Chris had work, but next episode will surely be almost entirely he and I reacting to this one).

Please share this episode far and wide and consider a paid subscription, it’s our only source of revenue here at Worcester Sucks and for a number of reasons, our subscribers are the only reason we can take on stories like this: Subscribe / Tip Jar.

A few weeks ago, Heather posted a video reminding people that the political class of this city continues to protect John Monfredo, the politically-connected school administrator who serially raped her when she was a child. Monfredo engaged in an escalating pattern of grooming and abuse over a three-year period. It started in 1991, when Heather was just nine years old, an elementary school student. In 2023, Heather and I collaborated to publish a full, detailed account of her experience with Monfredo, her unsuccessful attempts to appeal to authorities and the long campaign of character assassination carried out by the local power elite: “John Monfredo’s “teen-age accuser” takes her power back.”

After Heather released the video, Tom Marino at This Week In Worcester released an article that provides several of the most key advances in the story since Heather and I first released it back in 2023: “Worcester Woman to Voters: Reject Candidates that Protected Alleged Child Rapist”

Among several interesting threads is the establishment of a direct social relationship between Monfredo, then-Mayor Ray Mariano and then-District Attorney John Conte. Marino writes:

Conte, Mariano, and Monfredo not only share the same faith, but were also all active within the local Catholic community in Worcester. The three also shared long-time friendships.

When Mariano won election as mayor for the first time in 1993, Monfredo actively supported the campaign.

In January 1997, the Worcester Public Schools placed Monfredo on leave pending the criminal investigation and the school district’s own investigation in response to Prunier’s claims of abuse. Soon after the investigation began, the Telegram and Gazette reported on Monfredo’s suspension.

With the investigation ongoing, then-Mayor Ray Mariano provided comments to the Telegram supportive of Monfredo, including expressing a high level of trust in him, including with his own daughter.

The same article quotes Monfredo saying he was never alone with the girl who filed the complaint. He maintains the same position today, which Maureen Binienda has repeated many times to several people.

During Mariano’s tenure as mayor, his two-person support staff consisted of Rob Pezzella, a current candidate for city council, and Diana Biancheria, a current school committee member aligned with Binienda on most issues.

Then, on Oct. 24, the police department finally released a cache of investigatory records from Heather’s file. The release includes 10 investigative reports from 1996-1998, all summary documents of interviews WPD detectives conducted with Heather, her parents, multiple administrators, and a janitor at the Belmont Street School.

It took 18 months and the help of lawyers from the Harvard Cyber Law Clinic for Heather to receive these documents—to which she’s legally entitled. But the release is still partial. The extent of the records missing from the initial release remains unknown, but Heather said she’s committed to getting the rest. She says in our interview (about 46 minutes in):

... the fact that I have to do this is traumatizing. But also, they are my records. And I am entitled to them. And I get to have them. So don’t tell me I don’t. And what about the decades and decades of survivors who have been just dismissed? It is unacceptable that our public officials are not being held to task. These are our records.

We spend significant time going over the ins and outs of what continues to be a frustrating bureaucratic quagmire.

Though incomplete, the content of the documents provided offer an interesting glimpse into the time between Heather first coming forward to authorities, detectives mounting a case ,and then, the case against Monfredo somehow disappearing as the superintendent allowed him back at work, which in turn allowed Monfredo to claim exoneration despite never having been legally exonerated.

Of note: at least one investigative report in this cache was filed after his return. A document from 1998 is included. Monfredo returned to work in April of 1997. This means police were still investigating Monfredo after the superintendent allowed him to return to work.

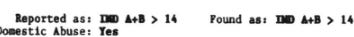

One of the records provided seems to imply the WPD were preparing to press charges. An incident report from January 29, 1997 lists Monfredo as the suspect and includes formal language around a charge listed as “Ind A+B > 14.” The report reads that it was both “reported as” indecent assault and battery and, next to it, “found as..”

The “found as,” according to multiple people with knowledge of the lexicon of these reports, indicates detectives believed they had evidence enough to build a case. The process from there would have been to submit the findings to the DA’s office, who make the final say on whether to charge or not charge. It’s a new development, this “found as” language: detectives were preparing a case, got far enough that they interviewed at least half a dozen people, then something happened and the case went away.

The same document recounts, in detail, a conversation with the lead janitor at the Belmont Street school where Monfredo raped Heather several times. In the interview, the janitor confirms key details from earlier testimony provided by Heather and her parents. And the janitor explicitly says that Monfredo was known to be there “at any time,” had keys to the entire gym area, and that there were days when the school was completely empty save for Monfredo and his softball team. All of it, down to small details such as the rain buckets from a leaking roof, confirms the account Heather shared with me over a series of interviews in the lead up to the publication of the 2023 story.

There are a few lines about Monfredo having keys that are worth including here in full.

Mr. Caffone said he usually saw ten to fifteen girls and a couple of parents in the gym. Mr. Caffone said that the girls used the bathroom facilities on the same floor as the gym. There were lavatories in the locker area and also just outside the gym area. All bathrooms and rooms in the school were locked and Mr. Monfredo had the keys. These rooms were locked up when Mr. Caffone returned for check on Sundays.

At the time, the janitor’s testimony—which, remember, has never before been made public—was a key component in Monfredo’s public exoneration, used as the basis for his claim that he was never alone with Heather.

About 29 minutes into the interview, Heather says...

I was told at the time that the custodian, when they interviewed him, contradicted what I said. And that that there was no opportunity for him to be alone with me, is what I was told.

Several of the documents challenge the line from a different angle. Three reports—one from Heather, one from her mother and one from her father—reference several occasions Monfredo drove Heather to her house. Two reports referenced instances in which Monfredo invited Heather to his house to go swimming. These are identical to the account Heather shared with me ahead of the release of the 2023 story.

Under Massachusetts’ public records law, documents pertaining to investigations into sexual assault are to be made available to the victim upon request. The language reads:

…all such reports shall be accessible at all reasonable times, upon written request, to: (i) the victim, the victim’s attorney, others specifically authorized by the victim to obtain such information, prosecutors and (ii) victim-witness advocates as defined in section 1 of chapter 258B, domestic violence victims’ counselors as defined in section 20K of chapter 233, sexual assault counselors as defined in section 20J of chapter 233, if such access is necessary in the performance of their duties

But Heather maintains that the police department has not handed over all of the documents in their possession. There has been a back-and-forth quibbling over legalese that has dragged the process out.

In one document, filed by Detective Kevin Langhill on Sept. 2, 1998, there is a 14-name list of potential witnesses the police presumably interviewed or planned to. One was marked deceased and another five are represented in the 23 pages given to Heather. That leaves eight.

Another noted absence: there are no interviews with Monfredo himself, or then-superintendent James Garvey, who cleared Monfredo to return to work after telling the Telegram he “was informed” no charges would be filed against Monfredo. (Informed by whom remains unanswered.) There are no interviews with then-mayor Ray Mariano, who vouched for Monfredo publicly in the Telegram while the investigation was still technically active. In one article, Mariano is quoted saying:

“I personally have a great deal of confidence in John Monfredo,” Mariano said. “Nothing I’ve heard would make me

doubt his integrity. But any time a child makes an allegation, it indicates there’s a problem somewhere. My heart

goes out to her family because either way, there’s a problem that has to be dealt with.”

Now, Mariano is the Telegram’s lead columnist. Just last week, he had a column run pressing the three mayoral candidates about a range of topics, including school safety. Rob Pezzella and Dianna Biancheria, his personal staffers when he was mayor, are both running for office.

Other links:

Sue Mailman bringing it up at school committee

Midland parents have had enough of John Monfredo

∿This podcast is available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Overcast, Pocket Casts others via this RSS link.

∿All music by me (Bill Shaner), written and recorded special for the episode. “Time Takes,” 11.3.25.

Help us spread the word! Use this to convince someone in your life to vote.