“I wish I had a magic wand and I could find you an apartment”

The cruelty continues unexamined

This post is about a homeless encampment eviction that I witnessed firsthand several weeks ago on a Wednesday morning. It’s taken me a long time to get it to a state worth sharing. The plan initially was to get something up later on the same day but it’s turned into a longer and wider interrogation. Like so many of these posts lately this is a magazine-length essay which I’d encourage you to take your time with. At 10,000 words it’s a book chapter (might have to open in a browser as it’s too long for most email apps). And while we’re in preface mode might as well ask that you kindly consider a paid subscription. Paid subscribers are the only thing keeping the Worcester Sucks lights on. And around these parts there ain’t too many lights like it if I do say so myself.

And if you can’t swing a subscription but would like to give me something, tips are appreciated! They can be sent safely and securely via Venmo! Haven’t offered this option before, which seems silly now.

Two quick plugs: The Roast of Worcester is tonight (Wednesday) and I will be roasting Worcester in front of a live audience with a bunch of people who are actually funny unlike me. It’s at the White Room (under Birch Tree Bread) at 7:30 p.m. Come hang!

And also there’s an important meeting happening tonight. The Standing Committee on Economic Development is holding another hearing on the proposed inclusionary zoning policy, which could either be good or useless. It takes place at 5:30 p.m.

Now to the main feature.

“I wish I had a magic wand and I could find you an apartment”

I spent several hours at the site and I had more than enough notes and audio recordings and observations to put together a very real-to-life account. I sat at my laptop from about noon to 9 p.m. in an effort to do so, but any progress I made was washed away by feelings of dull anger and dread and despair that I carried from the eviction back to my desk. The more I sank into the material, the more acute the feelings became. The piece of journalism I’d intended to write—a matter-of-fact dispatch which brought the reader into a specific moment that demonstrated the inherent cruelty of the city’s policies—became more of a diary entry. A sort of treatise on futility, I suppose, but a sophomoric one. Really it was just a temper tantrum. Not worth sharing.

Reading it over the next day conjured a childhood memory. One time at the beach as a little kid I built a sand castle that was gorgeous and triumphant to me in that moment, such that it still stands in my memory as an early feeling of true artistic self-fulfillment. When the tide started coming in I was so confident in my sand craftsmanship I earnestly believed I could save the castle from it. I was smarter than the sea. I knew it. I designed the most complex and impregnable set of sea walls and moats and jetties I could muster and looked out at the encroaching tide as if to say ‘your move buddy.’ As the tide started to lap against my defenses and dissolve them, I furiously repaired and rebuilt as a knot of panic swelled in my chest. I pushed myself to physical exhaustion. When the sea finally took my castle as it was always going to I completely broke down to angry and inconsolable tears. I knew it to be a personal failure. I could not be convinced otherwise or consoled or made to realize that success in this endeavor was impossible. For the rest of the day I stewed over the flaws in my battle plan and imagined ways it could have gone different.

Like kids do, I moved on pretty quick and forgot all about it. I never tried to save a sand castle like that again and I eventually learned to accept that the fun of building them is not significantly diminished by the fact they don’t last forever. But I’m not sure I ever agreed to the fundamental terms and conditions this moment presented. I haven’t truly conceded that sand castles can’t be saved.

I understand that to believe they can be saved is irrational and unjustifiable by logical argument. As a practical concern, the sea cannot be fooled. An immovable aspect of reality. But I don’t believe it. In the moment before I knew it to be crazy—when I really thought I had the sea figured out—I felt a sense of optimism and purpose and pride strong as the ruinous crash of failure. But if in that moment of defeat I made the compact with reality that my goal was fully irrational and success was impossible, wouldn’t it then stand to reason those feelings were irrational as well? And if I signed on the dotted line that reality slid across the table in that moment, would it mean I’d lose the ability to summon that sense of purpose I’d felt?

So I think I decided it was better to be a little crazy. To not accept that the sea cannot be fooled despite a working understanding of the obvious truth of the matter.

This is all a little inwardly focused for a piece that’s about how people who have it worse than me are treated. Fully aware. But this little detour into my own brain is here to serve of a wider point—one which goes tragically unaddressed or interrogated in almost all writing on a longstanding and pervasive issue like homelessness.

So many societal problems can feel as immovable and unfoolable as the sea. But they are not the sea. They are things created by humans and as such can be changed by humans. Homelessness is one of these things. Ursula K. Le Guin said it best:

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.”

It’s important to remember that homelessness—much like the slow destruction of public schools we covered the other week—feels immovable. A set of conditions which the individual can avoid experiencing but the society as a whole cannot avoid producing. And because the production is inescapable, the individual cannot escape the threat of experiencing it. Someone somewhere is always homeless and if you don’t play your cards right that person could be you. The threat is more immediate for some people than others and opinions vary on whether it’s a moral or just or fair threat but the threat itself is assumed. Inescapable as the tide.

This is the starting point for almost all public policy, journalism, scholarly study and works of fiction on homelessness. Good faith or bad faith, righteous or cruel, so much rests on the assumption that homelessness is inherent—a possibility among all the other possibilities of life in the real world. To look at this possibility as something less than inherent—not the flow of the tide or the sun or the slow creep of death, but something manufactured—requires a framework so abstract it’s entirely irrational. Policy proposals from this framework are easily written off as “unserious.” Such narratives are “absurd” or “naive.” Legitimacy rests on the tacit concession that the problem is inherent. It can’t be truly solved. Mitigation is the only achievable goal. The underlying disorder is made invisible in this way. We preclude ourselves from the lines of questioning which are likely the most useful.

And then there’s the consideration that maintenance of an order requires threat of consequence for not participating. There needs to be an “other” which you could become should you fail. These others are the unhoused, the insane, the imprisoned. The manufacturing of these others may not be conscious on anyone’s part but they are quite useful for those with a vested interest in the maintenance of order. To eradicate consequences is to devalue participation. Not something you’d go out of your way to do if you value the individual’s participation over their quality of life. In this way homelessness is not merely a byproduct but a value proposition. In the threat of it lies a certain coercion that has its uses.

In the broadest and simplest strokes it's the system of capitalism we live in that creates the conditions for homelessness to appear an intractable feature of modern life. It is the impulse to unfetter capitalism’s path that allows for things like the Old Sturbridge Village charter school to be a transparent grift of public money and receive state approval like we saw earlier this month.

It’s by these same conditions it becomes hard to imagine ways in which the problems could be fixed or even lessened. The idea of even making conditions for the unhoused less inhumane can feel like fighting the tide. When something feels like such a fixture of reality, it takes a certain amount of irrationality to consider how it could be different. Those committed to keeping it the same will quickly condemn such irrationality. There is a vested interest for people, especially those in power, for maintaining a perception that there isn’t anything to be done.

It’s up to us, of course, to combat that, and to risk the perception of irrationality in service of a vision of the world where everyone has a home and every kid gets a fair shake at things are in fact rational. There’s another Le Guin quote for that:

“I think hard times are coming, when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies, to other ways of being. And even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom: poets, visionaries — the realists of a larger reality. Right now, I think we need writers who know the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art. The profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art.”

The “realists of a larger reality” is among the terms most packed with satire and critique and meaning I’ve ever read. That’s just genius at work.

For me, the first stab at a post was analogous to the temper tantrum I threw when I lost my sand castle. I pressed and pressed on the question of “why?” expecting that I’d arrive on a novel answer which of course never came.

For a lot of people, the recent fight against the charter school proved a process of realizing that without hands on the meaningful levers of power, “public input ” is quite useless. You can make all the best points in the world but the vote is still going to be 7-4 the other way.

So on that Wednesday morning here’s what I witnessed.

Employees of the city’s Quality of Life Team and police officers forced a small homeless encampment near the Blackstone Valley Heritage Visitors Center in South Worcester to clear out. They didn’t help clear it out at all.

One of the residents of the camp lugged two trash bags full of stuff past a couple cops and Quality of Life team members who watched idly. He said “If you guys are kicking us out can you at least use y’all’s muscles” and the cops stayed motionless. They looked at him and grinned.

The cops and city employees didn’t help but they made it known it was to be cleared out and they watched it get cleared out while leaving the bulldozer running idle next to a dumpster the entire time I was there. Because the city gave advance warning that the camp eviction was coming, a group of activists who have a direct line of contact with the camp residents rallied to help them move in ways the city officials would not, and negotiated more time to do so before they brought in the bulldozer. They also made me aware of the eviction and invited me to come witness it.

A line of volunteers marched up a hill to the camp where they were helping the people living there break down their tents and pack up their belongings. Cops watched on as people trucker bags from the camp to their personal cars and loaded them up. Outreach workers from the Department of Health and Human Services peeked into tents and reminded people in them that they were there to help. They could connect them with what services were available. Of course they weren’t helping them pack and neither were the cops. That sort of helping was reserved for the small team of volunteers and if they weren’t there it would be on the residents and under threat of the incoming bulldozer.

What usually happens is the cops show up and tell the people at the camp they have 20 minutes to get their stuff out and then the bulldozer’s coming in and everything is headed for the dumpster.

Instead, this time, by the intervention of activists, the bulldozer idled while the volunteers and residents spent some three hours breaking down the camps. It’s not something that could have possibly been done in 20 minutes.

“What was the plan before this?” I asked one of the volunteers. “Just bulldoze?” The volunteer said, “That’s why they call it a ‘sweep.’ They literally just plow over everything. Everything is trash to them.”

This particular group does a lot to help the unhoused in our city and they deserve far more credit than they’ll ever get and they approach their work from the remarkably novel standpoint that unhoused people are human beings who deserve respect as such. They also requested anonymity in this story and will hereby be referred to simply as “the activists” or “the volunteers.”

Also, while we’re on the subject, I’ve decided against using the full names of any of the unhoused people I quoted. In past articles I’ve used first names and sometimes full names when quoting unhoused people. I believe that their perspective should be the center of the story and putting real names and faces to quotes is a way of achieving that. But several things I observed at the eviction last week and gleaned from subsequent conversations have led me to believe that the pros of granting that sort of dignity in the narrative are outweighed by various cons which all boil down to the fact these people are actively hunted by the police. So I’ve decided to use initials for attribution and decided against sharing any of the pictures I took. In this story you’ll hear from “C.” and “D.” and “S.” They are real people. They all consented to the use of their real names in this story. They all consented to having their picture taken. Their perspectives are valid and worthwhile and “credible” as anyone else’s. That I’m worried about the unintended consequences of granting them the narrative legitimacy they agreed to—and that I so badly want to give them—should stand on its own as an example of the fundamental cruelty toward the unhoused that we’re made to passively accept as an unavoidable reality. With all the freedom I have in this newsletter to consciously break the power-serving conventions of local journalism and with all the hard-won observations of how said conventions contribute to the perception of the unhoused as invisible and inhuman, it would be foolish and selfish to gamble another person’s safety on the belief that challenging harmful narrative conventions is a worthwhile enterprise. High risk, potentially no reward. I’ve done that in the past and there’s no changing it and I hope it hasn’t caused anyone harm... but when you hear from these people about how the cops lie to them and try to track them down and hang them up on any little thing they can and just make their lives as miserable as possible... the prospect of accidentally contributing to that routine cruelty is a far more pressing concern than any abstract media critique I could build into my writing.

In this city we are consistently reassured by the relevant officials that the strategy as it relates to the unhoused is rooted in compassion. “Offering services.” “Connecting people.” “A helping hand.” But that narrative does not at all jive with the reality I’ve personally witnessed or the personal stories people have trusted me with. There is so so so much in the way of truly understanding the reality of how a municipality like Worcester approaches the unhoused. There’s even more in the way of just plainly understanding that the people subjected to it are real human beings.

The process of staring into this void since the eviction has thrown me headlong into a depressive state and writing about it in a way that feels productive has proven difficult.

The reason for that I think is there’s nothing to point to. There’s no real better practical model to reference. There is nothing Worcester is doing especially wrong compared to other places. Maybe in the minutiae but not overall. And in other places it’s much worse. In other parts of the country we’re seeing the idea of literal concentration camps bandied about as earnest policy suggestions.

The thing that’s proved so vexing for me is how unremarkable and routine the camp eviction felt. How for everyone involved it was business as usual. Emotions were not running high. It was no one’s first rodeo. Every unhoused person I talked to had been through this before and they were just grateful their shit didn’t get thrown in the dumpster this time. It was so inherently cruel and unfair and hopeless and flat out pointless. For the benefit of the property owner who complained, the “problem” of these people existing was moved to another property where another property owner will eventually complain, triggering the same mundanely cruel process of eviction. The “services” offered by the outreach people were for the most part declined, as they always are, because there really isn’t a remarkably better alternative to the tent. If there was, people would be taking it. And every time there’s a camp eviction most people don’t take the city up on the “services.” Because they suck. They are bad alternatives. The Queen Street shelter remains a dangerous place people avoid at all costs and the new Blessed Sacrament temporary shelter is consistently over-full and the housing vouchers really don’t work and meanwhile the cops are making sure that you’re in and out of jail as much as possible. But city officials still frame the failure of people to avail themselves of these “services” as irrational personal decisions rather than evidence against the services themselves. They take credit for having tried at all and that works because almost everyone middle class and up has been primed to view the unhoused as a nuisance more akin to rat infestations than as fellow human beings and they don’t really care what happens so long as it happens out of sight and nowhere near their neighborhood. The unhoused, if visible, are bad for the perception of the city and bad perception means bad property value. The subtext of homelessness discussions on the municipal level are very rarely earnest examinations which center those who’ve fallen victim to it. However they are frequently and reliably framed around the physical evidence of homelessness and what that does for the perception of the city. This being Massachusetts and thus a Nice State the sentiment is rarely stated plainly. It would be quite untoward to do so. But to a careful listener it’s pretty obvious that the real issue is having to see homelessness. Not the hardship of unhoused people or what put them in that situation. And most of the time that seems to be rationalized by way of considering the overall issue of homelessness as too big to be dealt with, whereas visibility is something a municipality can manage. But that’s a concession which obscures the real project.

Really what’s happening is there’s a class of people who City Hall feels they have to actually satisfy–the homeowners and business owners for whom homelessness is first and foremost felt as a “blight” which threatens property value. Outside of fantasy novels and role playing games, “blight” is a word that only ever gets used in relation to property value. You wouldn’t describe a messy kitchen in your own home as “blighted.” That would be extremely weird. Or if you got a stain on your shirt at dinner. Sicko shit to use “blighted” in that context. My shirt is blighted. However if you describe a public park with some visible tents as “blighted,” everyone would know what you meant right away and understand the problem you’re identifying and the obvious solution and no further explanation would be needed.

Like I said this isn’t Worcester this is everywhere and “blighted” is one of those terms you can really chew on in a “Politics and the English Language” sort of way. It can be used to lift up the proverbial hood and really look at the whirring engine of state coercion and consent manufacturing underneath.

What happens is that “blight” is woven into the fabric of our values and politics in such an invisible and encompassing way that you really can’t put together a sane argument against it. You’d have to be brilliant or not care if you sound crazy and I am firmly in the latter category but hear me out. “Blight” is an inarguable problem for a city government to address and the visible presence of the unhoused is inarguable evidence of blight. The “dignity of every human being to be treated as such” is not so unconsciously baked into the value system as “blight.” Dignity is an open question, although it’d be uncouth to say as much directly. But people say it all the time in so many words... Depending on how big an asshole they’re willing to be they’ll say it right out loud. Or they position a term like “drug abuse” so as to tacitly ameliorate the “humanity” concern. Mostly though it’s in the subtext. It’s insinuated. An unspoken assumption under-girding the rhetoric. But it’s not a hard thing to pick up on. And however you say it “why should I value the human dignity of the unhoused?” doesn’t make you sound crazy like “why do we care about blight?” makes you sound crazy.

And so if you really think about the subconscious and unspoken difference in the politics of the two words—”blight” and “dignity”—you can start to see how a municipality is propelled to treat the unhoused as blight first and as human beings second. Thus the consideration of property, in which the unhoused are firmly “blight,” is put above the consideration of the unhoused as people who deserve to be seen as such in policy and treated as such in practice. This uneven dynamic can for the most part go unaddressed. No one has to say it out loud and it would a gaff to do so in most instances. But when a situation forces “blight” and “dignity” into conflict, like when a property owner complains about a camp, you bet your shiny behind it’s “blight” that wins every time.

So in the context where “blight” is assigned the unspoken upper hand, all the overtures you hear from city officials about their humane and helpful approach to homelessness are tacitly couched in that power dynamic. Compassion for the unhoused is fine and good to a certain point. But it ends exactly where the grievance of a property owner begins. Once a property owner is aggrieved, there’s no compromise to be made there. Whether or not the party is really being put out by a few tents in the woods is an impossible question to consider. The property owner is satisfied first and without compromise. Compassion for the unhoused comes second if it comes at all. It is enough to have tried to help the unhoused but unacceptable to have only tried to satisfy the property owner.

In all three of the camp demolitions I’ve covered, the process was triggered by a complaining property owner. In the Walmart demolition, it was the most dystopian as Walmart the evil corporation was the complaining party that the city felt duty-bound to satisfy.

It is almost always the case that these things start with some sort of complaint. The idea of not responding to such a complaint is out of bounds. Entirely irrational thinking. But the fact it’s so ridiculous to consider an unhoused person’s right to exist as having any sort of leverage against the grievance of a property owner is just another symptom of the inherent cruelty that reinforces the very existence of homelessness. Another example of the conditions which produce that reality. Like Le Guin said it’s something that feels immovable like the divine right of kings but is created by humans and can then necessarily be dismantled by humans. It is irrational to consider that homelessness is a byproduct of the very concept of private property. That one produces the other as a rule. But allow yourself to think about it in the abstract for like one second and is it really that crazy? Are there not housing units sitting vacant in our city while people live in tents? And what is it exactly that allows those units to remain empty amid such need for them?

There are alternative approaches. Homelessness is a solvable problem. There are possible sets of practices which aren’t so cruel and destabilizing as the current ones for the people made to experience them. Worcester is large enough to have a real and consistent unhoused population. But it’s not so big that experiments in approach are unfeasible. We could explore new ideas and show real leadership on this issue.

But any significant change which could be seen as an incursion on the expectations of property owners is way out of bounds here. No one is willing to touch that line. To do such a thing would take real leadership and genuine commitment to a vision. Both of these things are disincentivized by what we might generally call corporate culture, where success is contingent on “playing the game” and a reliable way to lose said game is by letting on that you’ve thought critically about whether the game is worth playing. The dominant political class in our city is as beholden to that culture as any outfit. Critical thinking is not incentivized. Playing the game is very much incentivized.

There was a brief moment in time some months back when the idea of sanctioning a plot of land for the unhoused to use without consequence was floated. It gained enough traction that City Manager Eric Batista felt compelled to weigh in. He used the opportunity to demonstrate he plays the game. From Neal McNamara at the Patch in an article from last September:

Batista in late August appeared on the Talk of the Commonwealth radio show, where host Hank Stolz asked if sanctioned camps might be on the table. During the interview, Batista noted campers had already returned to the Providence Street area after the American Legion sweep.

But Batista also didn't endorse setting up a sanctioned camp, conjuring images of one of the largest outdoor homeless communities in the U.S.

"Do we allow an area like a Skid Row in Los Angeles?" Batista said. "Is that something the city of Worcester wants to have?"

And so an idea that might lessen the abject cruelty of routine camp evictions was deemed beyond the pale and the brief moment of considering it faded away.

The City Council last week discussed the issue of homelessness for a few minutes in a diffuse way, but of course the idea of a sanctioned camp wasn’t entered into the record and neither were any new or promising ideas. Kate Toomey did take the moment to embarrass herself though so that’s something I suppose.

Toomey injecting herself as a protagonist is good satire but it’s not going to make anyone’s life better. At most it sort of demonstrates why no one’s life will get better. On this issue that’s really the best we can reasonably expect right now. There was no concrete demand made of the administration and even if there was the administration actually meeting the demand would be an open question.

Toomey was one of several councilors during that discussion who did the classic Worcester thing of blaming “the towns” for the problem. The implication is that the city is being put in an unfair position because the unhoused from all “the towns” are being “sent here” and what needs to happen is “the towns need to step up.” This is not a political positions so much as it’s a way of airing general grievances. Whether by willful ignorance or plain stupidity, this line of rhetoric demonstrates a failure to understand the geography of economic inequality. And it doesn’t stem from an impulse to earnestly solve the problems that create homelessness or help those who experience it. The problem at the center of this rhetoric is that homelessness happens here. The desired solution is that it happens somewhere else.

Outside activists and more progressive local politicians, the “why us and not the towns” position is the prevailing one. In this set of politics the unhoused are unequivocally “blight” and whether they are “human beings” is at best a secondary concern. As in all matters of “blight” the chief concern is the visible presence. The most pressing goal is eradication. Success is measured in the thoroughness of the eradication. Once you can’t see it anymore, you’ve succeeded.

Looking at this sort of mindset with clear eyes—as I’ve been made to do over many years covering municipalities in Central Mass where its prevalent—the fascism at play is pretty obvious. A city’s reputation and are so bound up in the goals of municipal government. Perception of “niceness” drives property values which drives growth. Perception of “dangerous” or “run-down” or “crime-ridden” do the opposite. The pursuit of a more positive reputation pits cities and towns into a sort of competition, meted out in crime data and school performance and the price of a single family home. In this reputation game, “a homeless population” is not a group of people but a data point. The bigger the number the worse off you are. The goal is to get the number down and the visible evidence out of sight.

This is inherently dehumanizing. “Homeless” as a political concern is divorced from “homelessness” as a lived experience. The term is loaded with connotations tied to reputation which have nothing to do with individual unhoused people but everything to do with the grievances of those who wish their town was “nicer.” It becomes very easy then to make a scapegoat of the unhoused for a city’s declining conditions! And conditions are ripe for decline! And declining conditions only produce more homelessness! I think you see where this is going... as do the municipalities around the country considering concentration camps.

The scapegoating of the unhoused is a bipartisan consensus not some MAGA thing that Won’t Happen Here In Mass type deal. So is the unwillingness to consider real alternatives to the current cruelty.

The trouble in Massachusetts however is that everyone is more or less adept at not saying the quiet part out loud or appearing transparently cruel and almost everything that happens to the unhoused happens out of sight, out of mind. No one would ever flat out call the unhoused blight here in Mass. We’d condemn that sort of rhetoric. But there are a lot of more subtle ways of saying it when everyone knows what you mean and agrees with you.

The most obvious example of that recently has been the ongoing spat over the temporary winter shelter at the Blessed Sacrament Church along Pleasant Street. A group of neighbors have complained incessantly for months that the city would subject their neighborhood to such a thing. Just look at this passage from Neal McNamara’s story on a meeting in late January:

One man questioned Batista about whether Worcester should put homeless people on buses and ship them out of town. The man, who declined to provide his name, suggested Worcester take a cue from Republican Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who flew migrants to Martha's Vineyard in a swipe at heavily Democratic areas.

"Put them on a bus, send them to DeSantis," the man said.

That’ll show those Republicans! Being just as performatively callous with the human beings I don’t personally care for!

Most of the time though it’s more mundane like this next comment from a meeting in December:

"Why should we have it in our community and not somewhere different?" one man said, opening up public remarks on the plan. He added that the homeless would bring in "trouble, drugs and stuff."

Translation: As long as the problem is not something I am made to personally witness it is not a problem. Which is exactly what Toomey and the other councilors are saying when they say “what about the towns.”

The Outraged Neighbors are also putting up a fight against a proposal to convert a hotel in the Lincoln Street area into “permanent supportive housing” for unhoused people, which is much better than an overnight emergency shelter and certainly would be needed. It’s a solid proposal and it should come online as fast as possible. But not if District 2 City Councilor Candy Mero-Carlson has anything to say about it. In a recent Telegram article, she promised to fight this thing, but did so using the traditional City Council code words.

Mero-Carlson, who represents the area, said there have not been large community meetings related to the project, and the neighborhood wants the opportunity to talk with Worcester Community Housing Resources about it.

"This is not about a neighborhood being anti-homeless; this is about a neighborhood that's looking for answers," Mero-Carlson. "And unfortunately this has gotten off to a bad start with the neighbors."

They’re “not anti-homeless” just “looking for answers” as we so often hear people who are anti-homeless described. Later in the article, we get those things they want “answers” for.

Mero-Carlson said people have wanted more information about security at the property, whether the homeless residents would come from Worcester or from other parts of the state, and whether the project could start smaller. In addition, she said, residents wanted to know whether the homeless would need to be sober.

There it is again. The “other parts of the state” aka “what about the towns” method of subtle dehumanization as we’ve been over. And then the Telegram quotes a resident with the #2 method for dehumanizing the unhoused: drugs.

Bruce Hoffner, whose family owns real estate and a car dealership on Lincoln Street, said he already sees many hypodermic needles in the area and a stream of individuals heading to Great Brook Valley, appearing intoxicated on Lincoln Street later.

"These homeless people are homeless because of the drug addiction that they have; they're not homeless because they lost their job or so forth and so on," Hoffner said.

The car dealership owner has an opinion on which unhoused people deserve what kind of assistance! Bruce continues...

Providing the homeless with housing is doing more to hurt them than help, Hoffner said.

"They're not going to appreciate anything they have because they haven't earned it," he said. "It was just given to them, they're just going to abuse it."

This is awful and cruel and pretty par for the course in terms of how Worcester people talk about the unhoused. The sad truth of it is Bruce is much more of a “constituent” to City Hall than me or the majority of the people reading this and his views are more in line with the majority position. As currently composed and politically aligned, City Hall is not going to try anything more progressive or invest more money in solving the unhoused issue and it is certainly not going to examine the cruelty of its current practices. Nobody who has real sway over City Hall is thinking about how to help unhoused people without first considering how to eradicate the “blight” they present. This is the same reality presented in the affordable housing debate. No one in City Hall is willing to entertain an inclusionary zoning policy which would meaningfully create real affordable housing. Just as “blight” mandates mundane, routine cruelty to the unhoused, “growth” means that maximum potential profit for developers is non-negotiable.

That we have people right now making meaningful challenges to these two basic realities is remarkable and unprecedented. For the longest time—at least as long as I’ve been paying attention—these sorts of assumptions went entirely uninterrogated by a City Council and local media who were content to just feel like they were in on it. Part of the club and in love with the Tuesday night drama.

Our progressive city councilors and all the organizers and activists—like the ones that’ve been showing up to the Economic Development Subcommittee hearings on inclusionary zoning and the righteous group of people providing direct mutual aid to the unhoused I mentioned above—have done a remarkable job of something that’s hard to explain but worth it to try.

There are doors to the inner machinery of City Hall which had not been touched in many many years and so much of what happens here happens behind those doors. Every time local progressives demand the city do better on a given issue and the city defends itself, we get to peek behind those doors. This is especially true when the city wins and the city has pretty much always won. Every time they win, they do a few things to different degrees. They lose the moral argument, they show who’s perspectives they actually value and who they’re content to ignore, and they give us a glimpse of the undemocratic and private process by which the significant decisions are made in advance of a public City Council process that is very often mere theater.

If we’re ever to do something about the mediocrity of City Hall and the feckless deference of the City Council and the quiet violence of the Police Department and all the nice things they preclude us from having, we must first understand what’s really in the way.

That’s the ball and it is extremely hard to keep your eye on it when every week the city is just sucker punching you in the face cuz they can while saying I’m not hitting you you’re hitting me. It’s emotionally exhausting and frustrating to follow and I can’t even imagine how it feels for the progressive councilors made to take the brunt of it. When you’re always losing, it’s hard to see the progress made. But we have here an opponent which can only be clearly seen in a fight. Unchallenged, City Hall gets to set the confines of rationality. What can and can’t be expected. The irrationality of fighting battles which can’t be won shows that this rationality is not an absolute but a product of the self interest of those in power. A human construct. Not the tide. We have in November the opportunity to get a progressive majority on the council. Just three more seats. And at that point this rationality can be actually challenged and redefined. We can start winning. It’s a realistic outcome. In this current moment of being bludgeoned by mediocrity it doesn’t feel that way. Really it’s hard to feel good about anything at all lately. It seems like everyone on earth is operating on the baseline understanding that things will surely get worse. Just a matter of how fast and how acutely we feel it.

But I do think we have an opportunity here in this stupid little city to prove that against the wider tapestry of anxiety and gloom a tiny piece of the status quo can be upended. That it’s not so irrational to care and that caring is not always punished. Caring can in fact be rewarded.

Amid all that, let’s take a look at this one specific homeless camp eviction and how the city went about it.

The camp was in the general vicinity of the large encampment behind Walmart which was cleared out in the fall of 2021 and another encampment on the other side of the highway called The Mountain, which is up some high tension wires behind the American Legion Hall, and was similarly cleared out last August. These are three locations I know about because I’ve written about them, but there are many other homeless camps in the general area of the Walmart exit. Whenever there’s a camp eviction, people naturally migrate to another one of these locations. This was not the first eviction for anyone I interviewed. So the act of evicting camps only serves to shuffle people around the established camp sites in the area, thus preempting another eviction at another time. Everyone I talked to Wednesday was sure of this.

The camp was a small one and, especially compared to the one behind Walmart, it was quite out of the way.

The site was up a small hill between a fence bordering Dennison Lubricants, some railroad tracks, and the Blackstone River. As was the case with the Walmart demolition this camp is in view of the relatively new walking paths installed in this park and much celebrated by city officials and as such it could be seen by people who City Hall may assign value.

When I arrived on Wednesday, there were two large 10-12 person tents being used by three people total, as well as two plots where it looked as if tents had recently been, and a smaller one-person tent up against the fence. In total, there were four people living at the site at the time. Possibly five. But on any given day it could have been more or less. By the looks of it, there were at most six tents at this site at any given time. One of the tents there looked as if it was abandoned a while ago. It had folded in on itself and was enveloped in a pile of trash around it. There were several mounds of trash on the site that were mostly clothes and tent materials and the remnants of gas stoves and takeout containers.

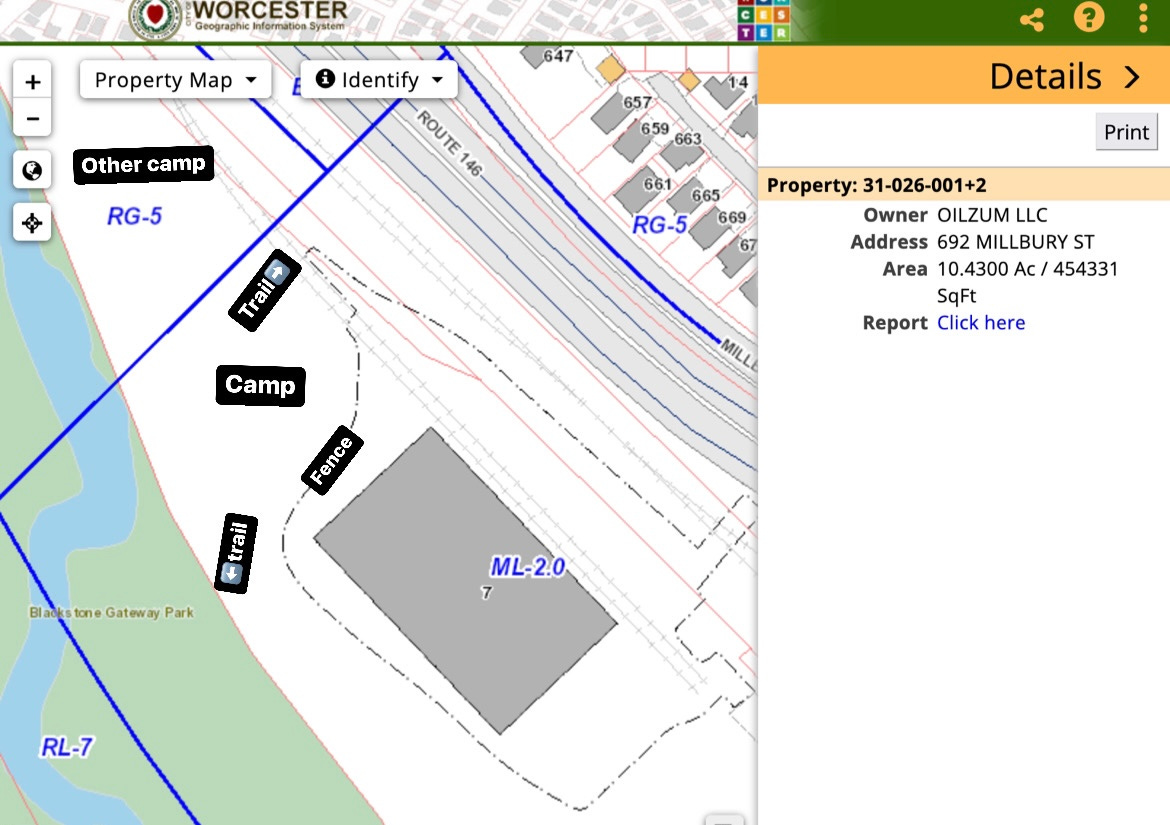

Below is more or less where it was, as shown on the city’s property mapping tool and crudely marked up by yours truly in the Instagram story editor (real professional news outlet we got here eh?).

There was some question from people on site Wednesday whether Dennison Lubricants actually owned the property the camp sat on and the cops did not necessarily have proof of it. One of the activists asked for proof and the cop waffled saying something to the effect of “I can get you that” but he never did.

City property records as seen above show that the entire tract of land is owned by Oilzum LLC including the site of another camp further to the north which was not being evicted at that time. Everything in white within the red lines is Oilzum property. Kind of a side note to the overall thing here but the relationship between Oilzum LLC and Dennison Lubricants is unclear. Dennison’s website lists Oilzum as a brand. But nevertheless the building seen here on the other side of the fence from the camp is the Dennison Lubricants building and city officials treated them as the property owner. This is potentially a little less than true but probably true. In any event it was true enough for the city to act. According a city spokesman, the camp was cleared because Dennison asked them to clear it.

“The property is private (Dennison Lubricants) and they asked for the City’s assistance in connecting individuals with resources and services as they cleared it out,” the spokesman said via email.

It’s technically true that the land is private and that it’s owned by Dennison (or Oilzum, if they aren’t the same thing? IDK). The subtext of the city’s statement is that the encampment would have been cleared either with the city’s assistance or without it. Whether or not that is actually true did not prevent the city from helping make it true. So it’s just true in the end.

What remains unclear after being at the site is how people living in tents on this particular plot of land at all impeded Dennison’s business. The campsite was up on a hill on the other side of a barbed-wire fence that seemed to indicate the boundaries of what Dennison considered their property, or at least the usable portions of it. You can see this fence quite clearly on the map. The dotted line around the building. There were no signs indicating that land beyond the fence was private and that going onto it is then trespassing. Just for me personally when I see a fence it is an assumed marker of property boundaries. Why would someone put a fence through the middle of their own property?

Nevertheless this camp was on Oilzum property legally but it was not land that seemed to have any immediate use for the company. It is very hard to imagine what harm these people, who couldnt have ever numbered more than 15 at any given time, were causing this large oil manufacturing and distribution plant. If there were any designs for this small hill on the other side of a fence, they were not articulated. Not that such an articulation would be required for the city to act.

In both of the previous times I’ve covered camp evictions, city officials were quick to point out that there had been a fire at the site some time previous. This was no exception.

“There was a fire at the site about two months ago which vacated most of the area,” the spokesperson’s email read.

Fires are a public safety hazard after all and saying there was a fire is a good way of making it seem like there was some threat to public safety that needed to be remedied and whether or not there was a fire at a camp in the woods is a very hard thing to confirm. However in the three hours I spent talking to people at the site Wednesday no one brought up anything about such a fire and there was no physical evidence. When there’s a fire in the woods it’s usually quite obvious. There were many flammable things on the site which were not burned. I’m not going to take this line of inquiry about whether or not there was a fire any further like suggesting that the city is lying about something which can’t be disproven—that would be crazy!—but feel free to do so yourself.

Claims of fires aside, what was the threat to public safety here? Why was this a problem that had to be remedied? Why were these people made to move when no one close to the issue realistically believes they’re going to move anywhere but to a different camp in the immediate area?

The thing about what I saw this morning that’s really sitting heavy with me is it wasn’t some big operation, it wasn’t violent, it wasn’t unprecedented, it was just normal. A day at the office. And it’s only going to result in the same exact day at the office in some other place at some other time in which when the city sees fit to respond to a complaint. And they’re going to do it in the same way. And whatever modest accommodations these unhoused people had been able to make for themselves will be similarly upended. And they’ll again be set back to zero. And they’ll be in a new place where they will be harder for the people who actually care and actually help in some way to find them. And the alternatives to a tent will still be lacking. The “services” offered by outreach will be just as bad a deal. And when that day inevitably comes they’ll have to do everything I witnessed them do last week over again. And on that day there may or may not be the team of volunteers as there were in this instance who made it easier and bought them time to actually pack. They may not be there but the cops will certainly be there. There will certainly be a dumpster and a bulldozer. And the “problem” such as it is that these cops and outreach workers and bulldozers and dumpster are claiming to ameliorate will be no less a problem it will just be in some other place. And after they inevitably clear that place out it’ll be another place after that.

Nothing is getting fixed here. No one is getting helped. And from the perspective of the people living in these tents it’s just harassment they have to live with. A trial among trials that comes with homelessness. Just another cruel fact of life which keeps them in an untenable and desperate situation. Every time, they’re set back from square zero to a worse square zero.

And from the side of city government, which is ostensibly trying to fix this problem with its “quality of life team” strategy, the man hours and associated costs that go into these “sweeps” as they call it only create the conditions for future sweeps. If the goal is to keep creating new encampments so you have new encampments to eventually sweep, they’re doing a great job of that. But if the goal is getting homeless people into homes, that’s clearly not working. This policy does not create more housing or better temporary shelters or anything else that might constitute a stronger social safety net or a better quality of life for those falling through the cracks. All these “sweeps” do is satisfy the complaints of one property owner at the expense of some future property owner who will make the same complaints and be satisfied by the city in the same way.

What remains unchanged is the reality that for some people, living in a tent is the best available option. Until the reality changes, the best available options for people within it will not change. This is as simple a concept as supply and demand.

One of the unhoused people I interviewed was living at the Walmart camp when it was demolished.

“We were at Walmart,” said C. “They bulldozed right through our shit. Luckily we werent there that day. They bulldozed right through it.”

Every time, it’s the same, C. said.

“They pretty much come tear your shit up. I've been asked to move and been told where to move, set up a new tent, didn't even get to move into it, next day I go to move into it and it's all cut up by the same people who told me to move it there.”

There are trappings of our society which produce this reality. At best, the city sees these trappings as outside the its purview. Insolvable by the institution and thus not worth considering in the institution’s choices. Instead, they say they’re doing ~what they can~ with the ~available resources~. So they “extend services” to these people before forcibly removing them from their homes and it’s pitched to the public as an act of benevolence. Going above and beyond. Whenever they force people out of these camps, they call it a “point of contact” opportunity for the “services” toward which they “connect people.” Should someone decline to accept those “services,” their tent still comes down, of course. The “services” are voluntary whereas the removal is non-negotiable. But because they offered something, they get to frame it as a matter of personal choice should a person decline. It becomes their fault. That lets the viability of the services off the hook. They say “we just can’t reach these people.” And so the hardship caused by tearing down camps is obscured behind the portrayal it was the result of choices made by the people living there. The obvious reality is that the city’s job is to make vulnerable people’s lives more uncomfortable on purpose. But what the general public hears from the City Council and the mayor and the city manager and everyone else is that they’re trying to help. Doing their best. And if you don’t squint too long and don’t hear another perspective it’s not an unconvincing pitch. But for the people in the tents who are subjected to this “help,” there is a common understanding that the city workers and cops providing “outreach” and “services” are not there to help. They only hurt. And as such they’re to be avoided at all costs.

For S., this was the third camp eviction they’d gone through. At the last one, S. said the cops took down everyone’s names for the sake of such helping. For S., this led to a month-long stay in jail.

“They say do you want help do you want help and if you don't take the help.... the first time they came up and asked if we wanted to do detox and if we didnt take it they arrested us. I had a warrant and they ran my name. They said ‘we're not going to run your name we're not going to run your name we just need it for our records.’ And then they came down and arrested me while I was signing. I was in jail for a month. Yeah, that was sick.”

But we never hear that side of things. The narrators of that version story are not legitimate as a rule. Just as City Hall is happy to claim they’re “trying to help” against the available evidence, the local press is content to leave the assertion unexamined. The perspective of the unhoused is not a requisite for “balance” in the prevailing set of standards for “objective” reporting. Most of the time it’s simply ignored. Easier that way. The city’s perspective is dutifully relayed because the city’s perspective has an assumed legitimacy. The perspective of those experiencing the brunt end of it are not extended the same courtesy. Their experience exists outside the confines of legitimacy. Their comments are subject to a level of scrutiny which makes it very hard to reach the public, especially if it contradicts the narrative of the city. They are “unreliable narrators” until proven otherwise and it is mostly impossible to do that. Conversely, city officials are reliable until proven unreliable which they never are even if they lie. There’s no burden of proof to be met. Not in the same way.

So the prevailing narrative is not a reflection of reality as much as it reflects the power dynamics of the reality. But it’s conveyed to the public as reality and the power dynamics are obscured. In this process, people without power, like the unhoused, become invisible. So this dispatch of what happened Wednesday is a meager attempt at combating what I see as a failure of journalism to get this right. In this post, the perspective of the unhoused are held to the same standard as the perspective of the authorities.

At one point a cop came over and pulled out his notepad and asked me my name. I gave it to him. He asked me my date of birth and I asked why he needed that. He told me it was for the police report. I gave him my date of birth. The cops asked everyone this. The volunteers and the camp members. One volunteer refused to give his information and the cops told him to leave. They said he was trespassing. Another who similarly refused to give his birthday was only allowed to stay when he reminded the officer he was there with the permission of the property owner. The cops took down the license plates of the volunteers’ cars. I asked them if they were running the plates and they said no they just need the plate numbers for the police report. They didn’t explain what the police report was for exactly just that they had to write one. He asked me why I was there and I told him I was a reporter and he asked what outlet and I just said “independent” and he pulled his pen away from his notebook and walked away. I am confident he ran my name for warrants.

A health and human services worker mistook me for a camp resident and launched into the spiel about connecting me to services and I said no I was fine I was just there to help and a resident in the tent shouted out that I was a reporter and he wordlessly backed away.

I helped D. pack up his tent which was tricky because some of the tent poles had been broken and duct taped together and some of the hinges were cracked and D. told me that when it's really windy the tent is almost blowing over sometimes

I asked him about those really cold nights we had a while back.

“It was rough man,” D. said. “We have a propane stove for heat but it was so cold it wouldn't stay lit. It kept going out, right? And so we get that hand sanitizer, soak it in a napkin and light it on a dish. You light it and it'll burn for 15 20 minutes or so. But basically that's how we stayed warm.”

For a few hours, they went to the the warming station at the Senior Center that the city unveiled to great fanfare.

“We spent a couple hours there to warm up,” D. said. “We go and have lunch right, and I go and sit down with my girlfriend and she goes 'The city spares no expense!' What they had served was boiled hot dogs and what they said was potato salad. They cut up a couple potatoes, right, and just drenched it in mayonnaise and something else. It was... you know I ate it because I was hungry. But it was awful. I was laughing at that though—‘The city spares no expense.’”

The city does however spare no expense when it comes to demolishing camps. These demolitions happen all the time and for the most part we never hear about them.

Each of the residents I interviewed referenced a recent demolition of what they called “the off ramp.” I pay pretty close attention to these things and I didn’t hear about this one. According to S. they just bulldozed everything into the river. It was late at night and they came suddenly and they cleared it out quickly.

At the eviction I was present for, outreach workers were letting the unhoused in on a schedule of upcoming evictions. Like it’s baked into the schedule. The camp further north on the same piece of property was next, they were told. Then the camp behind the nearby Xtra mart. “The Mountain” would be cleared in the summer.

“I asked him I was like ... where can we go?” said D. “When we're by ourselves nobody bothers us. When a couple more tents go up, they bother us.”

Turns out “The Mountain” was moved up on this docket of routine cruelty kept by the city. Last Thursday, according to volunteers and confirmed by video recordings, 12 to 15 cops showed up in the afternoon and made everyone living at The Mountain clear out. The promise of staying there until summer was no more. Time to pack up.

In the video, a police officer is heard saying the following to an unhoused person they are forcing to move:

“We try not to be the bad guys. I wish I had a magic wand and I could find you an apartment.” the officer said. “It’s hard, I understand that. In the meantime, you can go to the shelter, you can go to one of the other shelters they have different services to help you with other things if you need help with other things.”

And then the officer turns to the volunteers and says “how about this, while I’m talking to him, do you guys want to start moving things so we’re not here all day?”

And just today I got another text saying another eviction is scheduled for later in the week. On and on it goes. No one is helped. Nothing gets better. And the cops are just hoping they won’t be there all day.

~/~

Woof. That was a long one! Thank you for reading! It took me a ridiculously long time to write. Please consider a paid subscription 🙂

Or send a tip via Venmo!

Or share the post too that always helps a ton.

In case you missed it check out my story on Problem Pregnancy in Teen Vogue! Pretty proud of that one!

Highly suggest reading also Tracy Novick’s recap of the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education’s demoralizing vote on the Old Sturbridge Village charter school.

And thus while I am at heart an optimist (I don't know that I could bear to do what I do otherwise) to some degree the vote at the end of February I suppose shouldn't have surprised me. The known motivations of a Board nearly entirely appointed by Governor Baker have been well-known, and largely have little to do with the largest concerns in public education at this time. (Let me note the quite marked exceptions of the Secretary, and the student, parent, and labor seats, as so often.)

We were respectful, it seems, but we were unheard. While I have, as a member of a public board myself, respect for processes of public procedure, gestures towards 'respect' may not be heard.

On a positive note congratulations to City Councilor Etel Haxhiaj for winning the Challenging Convention Award from Clark University! Well deserved if you ask me!

Dang. Worcester has “the largest infestation of adult spotted lanternfly in Massachusetts, according to the state Department of Agricultural Resources.” Time to get stompin’, people.

The weird legal battle over who should pay the $8 million wrongful conviction judgement to Natale Cosenza continues. From Brad Petrishen at the Telegram, who’s been following this like a hawk.

The city has argued that it is legally unable to indemnify the officers because of the manner in which the damages were awarded — an argument the city’s police supervisors' union head sees as “troubling."

“I haven’t been able to wrestle from the city administration where they’re going with this,” Sgt. Richard Cipro, president of Worcester Police Officials Union IBPO 504, told the T&G Thursday when reached by phone.

Cipro said the union is still trying to determine whether the city’s arguments in the case have broader implications that might need to be addressed in collective bargaining.

The broader implications here are of course police officers maybe being personally liable for ruining people’s lives on purpose, as was the case here. Cosenza was in jail for 16 years on evidence fabricated by Worcester detectives.

I finished reading Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian this morning and The Judge was dancing through my subconscious like a ghost. Entirely spooked. And then I happen to find that the guy Blood Meridian was sort of based on died in Worcester and I wanted someone to hide me. Too spooky.

Congrats to Femme, the new lesbian in the Canal District, for what seemed like an impressive opening! Has me thinkin’ about this Jonathan Richman song.

This will be me at some point in the near future.

Talk soon!

Good article. There isn't enough housing in Worcester for everyone who needs it. I used to work for Center for Living and Working, I used to assist disabled people with filling out housing applications. Once someone was on the waiting list they were there for months.

Fucking incredible and so sad and depressing.