Worcester's Literacy "Crisis" (Part 1)

First of a two-part examination of reading and writing in the public schools.

Thrilled to share this massive feature Aislinn has been hard at work on for months. This is the sort of in depth local journalism we love to see! Please consider supporting this outlet so we can continue to put out work like this.

Now to Aislinn. This story is long and has a lot of images, so it’s better to read in a browser than in your inbox.

Worcester’s literacy “crisis”

When Worcester went into pandemic lockdown, Olivia Hashesh’s son Abe was in kindergarten. Remote schooling was tough. He'd just turned five, and shared the house with two younger siblings, one three and one four months old. Abe did not understand why they got to play while he had to sit in front of a computer screen. Recently, I asked Hashesh about that time. “It was unrealistic to expect a five-year-old to stay engaged and capable of learning while interacting only through screens. He was just already so young for his grade. I was very worried he would fall behind,” she said.

Because his birthday is just seven days before the Worcester kindergarten cutoff of December 31, Hashesh and her husband had already planned to have Abe repeat kindergarten. When they realized that he was going to have another year of remote schooling—WPS did not have in-person school for most students until May 2021—they knew it was definitely the right decision. “I cannot imagine where he’d be if he had not repeated kindergarten. Remote school was just so challenging,” Hashesh told me. Despite the teacher’s best efforts, it was an impractical task that didn’t allow for teacher-to-student interaction and help in specific areas. “It was so hard to keep him engaged.” she said.

Now a fourth grader, Abe is reading above grade level, but that was not always the case. “It took him until the end of second/beginning of third grade for him to really find his footing academically,” Hashesh told me. “I definitely pushed him more than I do with my other two kids, because I was so worried about what he missed in those remote learning years.” And it’s not hard to imagine the result if her son had not repeated kindergarten and was currently in fifth grade. He might not be reading above grade level.

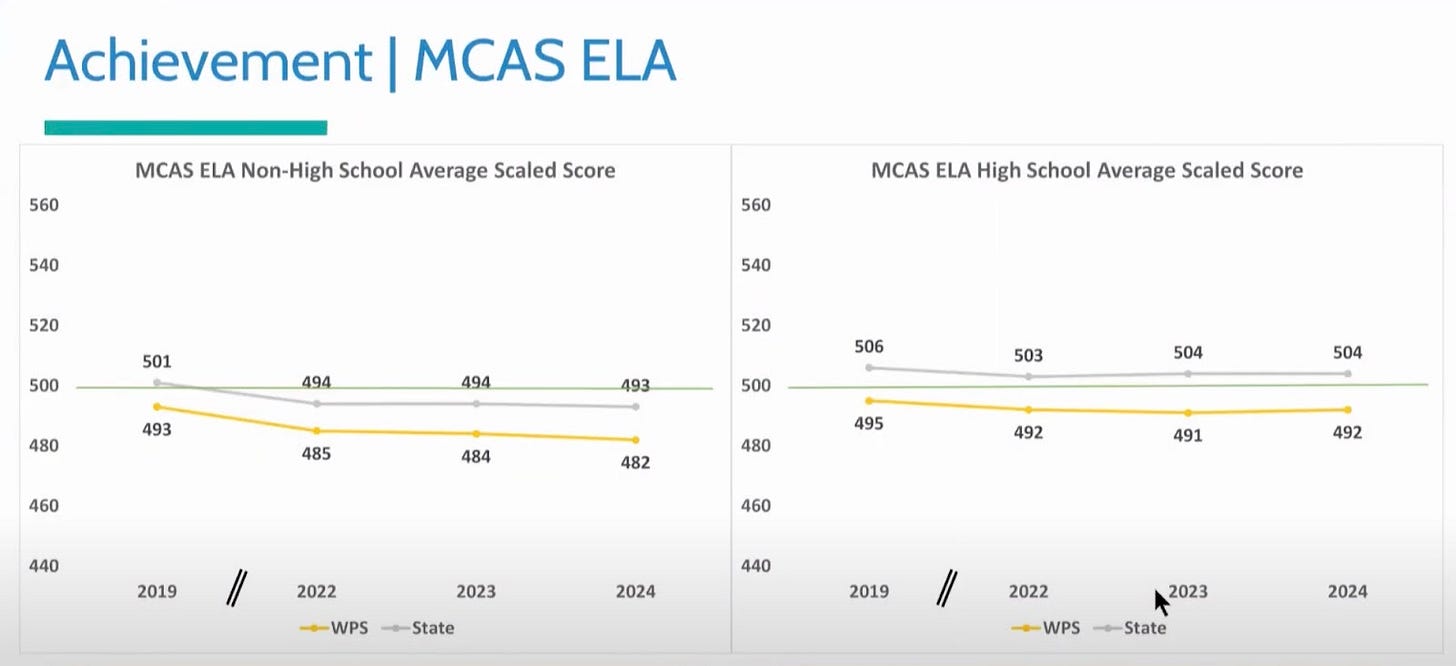

Olivia’s concerns about remote schooling are warranted, and not unique to Worcester. MCAS testing data for students across the state, and comparable data across the country, show that students are not performing as well as others did before the pandemic. Scores overall are falling. Gains are not being made back quickly. Fifth through eighth graders are seeing the greatest impact in test scores as compared to students in the same grades before the pandemic—they were in K-third grade in the 2019-20 school year—especially when it comes to reading. But in Worcester, the pandemic does not explain it all. Test scores were declining in Worcester in the years before 2020.

It’s hard to pinpoint why MCAS scores were declining—experts are trying to parse it out—and we may not know for many more years. But out-of-school factors have the biggest impact on standardized test scores (like language spoken at home, family income, and parent’s education), so it’s not a great measure of how a school system is doing. Worcester’s percentage of low-income students is high, at 71 percent, and the gap in test scores between rich and poor students in Massachusetts, alarming before COVID, is now half a grade wider than in 2019. This was the largest increase of any of the states studied—a disturbing fact for a state that likes to tout the “best public education system in the country.” Given these outside factors, it’s no surprise that the largest drop in MCAS scores is among low-income and Hispanic students (45 percent of Hispanic students in the district are also English learners.) In speaking to educators, they often point out that MCAS scores are just a single data point that don’t necessarily give the whole picture of where WPS students are in terms of literacy.

Worcester Public Schools Superintendent Rachel Monárrez emphasized that validity at the October 10 school committee meeting.

“I have to say when I look at these line graphs of how the state has done over time with MCAS and how Worcester has done, and we mirror it, it’s fascinating to me. And as a researcher I do have to question the validity of the assessments over the last few years. Because the data should not be going up and down like that. It makes me wonder, is it about how the children are actually doing or is there something deeper around the assessment. How interesting that we change as the state changes, That’s very uncommon. You wouldn’t expect to see that. For me as the superintendent of Worcester Public Schools, we’re going to chase learning in this district. We’re going to chase how our children are doing in the classroom each and every day. As the state figures out the accountability system.”

But that doesn’t stop the media and commentators from highlighting MCAS as the be-all-end-all. If you read the Telegram, MCAS scores often make headlines that lead us to believe we are in a literacy crisis1; and politicians and local nonprofits say that low MCAS scores are proof that our kids can’t read. There are podcasts and national news headlines emphasizing that scores are dropping and kids are illiterate. As a parent of early elementary-age kids, it’s hard to hear this rhetoric and not worry. Should I be concerned that my four-year-old can’t identify all the letters? Or that my second grader is horrible at spelling? Can I trust that Worcester schools are equipped to teach our kids how to read?

So I started talking to parents, teachers, principals, district administrators, and community members about literacy in Worcester. I started asking questions because I wanted to understand: If we cannot blame the current literacy challenges of our education system on the pandemic alone, what else is it? Is there something deeper? And the most important question: How do we fix it?

The literacy crisis.

The idea of a “literacy crisis” in Worcester has existed for decades—way before the MCAS, as demonstrated by the WPS parent quoted above. There was a literacy crisis in the 70s, the 80s, the 90s and the aughts. As historian Harvey Graff points out, the public discourse about a crisis isn’t based on empirical evidence, but comes from literacy being represented as “an unqualified good, a marker of progress, and a metaphorical light making clear the pathway to progress and happiness.” He adds that “the decline of literacy is taken as an omnipresent given and signifies generally the end of individual advancement, social progress, and the health of the democracy.” Graff points out that despite the lack of empirical evidence the myth still takes hold. According to the NAEP, aka the Nation’s Report Card, nine-year-olds in 2022 are still scoring higher than nine-year-olds were 50 years ago in 1971. Graff continues, “The myth is argued by anecdote, often rooted in nostalgia for the past, and selective reading of evidence. The myth of decline neglects the changing modes of communication, and in particular the increasing importance of media that do not depend completely on print.” Literacy as presented in public discourse is a social concept, full of our own fears. That we are losing a particular form of literacy, one that is “seen to represent a world that is at once stable, ordered, and free of dramatic social change…” One could argue that we’re trying to get back to the status quo of the pre-pandemic world, one that the MCAS does not measure.

And so the question becomes, are we in a literacy crisis in Worcester? How do we parse out the social fear from how students are actually doing in the classroom?

What is literacy?

When I asked this question of Erika Schmitt Boyle, a sixth grade teacher at Belmont Street Community School, she said “Of course the ability to read and write, but it is also thinking critically and analyzing texts, communicating in an academic, respectful manner, and being able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes to better understand and engage with the world.”

Literacy is how we make meaning of the world around us, the ability to speak, listen, read, and write. It allows us to communicate well and connect with others. But how that happens is very different today than it was 50 years ago, or even five years ago. What we read and how we read have both changed drastically. The skills to be literate in today’s world require interpreting and understanding content in a wide variety of contexts and forms—video, pictorial, aural, oral, and print—and communicating effectively in those forms. There’s no way to know how that will continue to evolve for the five- to 11-year-olds in elementary school today. And so preparing them for the future requires an evolving definition of literacy.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts has state standards that students must meet in order to move to the next grade. Mary Sealey, principal of Canterbury St. Magnet Computer-Based Elementary School, said the standards are the foundation of what students are taught in Worcester Public Schools. “All of our work here is focused on the standards, which are pretty rigorous. Reading and writing, communicating effectively, analyzing texts and pulling out evidence. That’s where we’re working to get students when they leave here in sixth grade.” The state has these great guides for families to help us understand what our kids should know at the end of each grade.

The district also has a broader Vision of a Learner roadmap and a five-year Strategic Plan that outlines literacy goals. Specifically, for the last two school years most elementary students have been taught using a curriculum called Core Knowledge Language Arts, or CKLA (dual language and bilingual education students use a curriculum called ARC). CKLA replaced the Fountas & Pinnell curriculum (F&P) that the district had used for the previous five years in K-3. F&P recently came under scrutiny after the release of the podcast Sold a Story, which questioned the curriculum’s theory of “three cueing.” Educators in Worcester, especially those working with a high percentage of English learners, also raised concerns that it was not working for their students. The district presented the new curriculum at a school committee meeting last November and emphasized that elementary teachers did not previously have high quality curriculum materials. The new CKLA curriculum solves that problem. For the first time, the whole district is employing a full language arts curriculum for all grades at the elementary level.

Still, a curriculum is only as good as the teacher teaching it. Second grade teacher Karen Campos has taught four different curriculums over her 16 years in Worcester Public Schools. For her, no particular curriculum has made a huge difference in terms of teaching literacy: “I believe that the most significant impact on teaching literacy is knowing the students that you have in front of you, providing small group instruction focused on what they need, while exposing them to all aspects of literacy.” And she’s right. Time and time again research has shown that teachers are the single most important in-school factor for better outcomes. Policymakers struggle with this, because they want to be able to easily measure how “effective” teachers and districts are, but there’s no clean and simple way to do that.

How do we measure literacy?

State legislators and school committee members love testing data because it’s “cut and dry.” You look at the numbers and see if they go up and down. But literacy is not a simple thing to measure. On the one hand, you have some basic skills that you can measure easily with quantitative data: if students know the alphabet or specific phonics sounds or you can count how many words a kid gets wrong while they’re reading. But things like background and content knowledge, vocabulary, and reasoning skills need to be measured qualitatively. The district uses a few assessments to gauge elementary literacy. Quantitatively they use DIBELS, Star and MCAS tests. Qualitatively it’s rubrics, listening to kids read, and taking running records, which is when a teacher makes notes about a student’s reading while they read aloud.

Report cards are one clear place where literacy is measured. On them, teachers use their professional expertise, including both qualitative and quantitative data, to assess where students are at. Massachusetts has state standards that each student must achieve in order to move on to the next grade and those standards are what students are graded on. At the top of the report card it is made explicit whether a student is at, above, or below grade level in reading and writing. As a parent, the primary way I know how my kids are doing in school is through their report cards, plus one teacher conference.

Because teachers use their professional discretion when filling out report cards, the data could help understand the district as a whole. I asked the district if it would be possible to get a look at the report card assessment data to see what percentage of WPS students are reading and writing below, at, or above grade level. A district spokesperson told me that “at this current time the data cannot be pulled.” That data would be ideal to gauge whether Worcester is in a literacy crisis. But we don’t have that, so let’s look at the data we do have.

Are we even in a crisis?

The two tests that the district can pull data from around literacy are what they call “universal screeners.” In WPS, teachers use these “screener” tests to help inform instruction and decide if students need additional support (what they call tier 2 or tier 3). Students who need additional support are monitored more closely for progress, whereas kids at or above grade level are screened three times a year: at the beginning, middle, and the end. The tests are: Star, which looks at reading achievement data and is a broader review of how children are reading at grade level; and DIBELS, which looks at reading growth, and focuses on more discrete reading skills, which are easier to measure2.

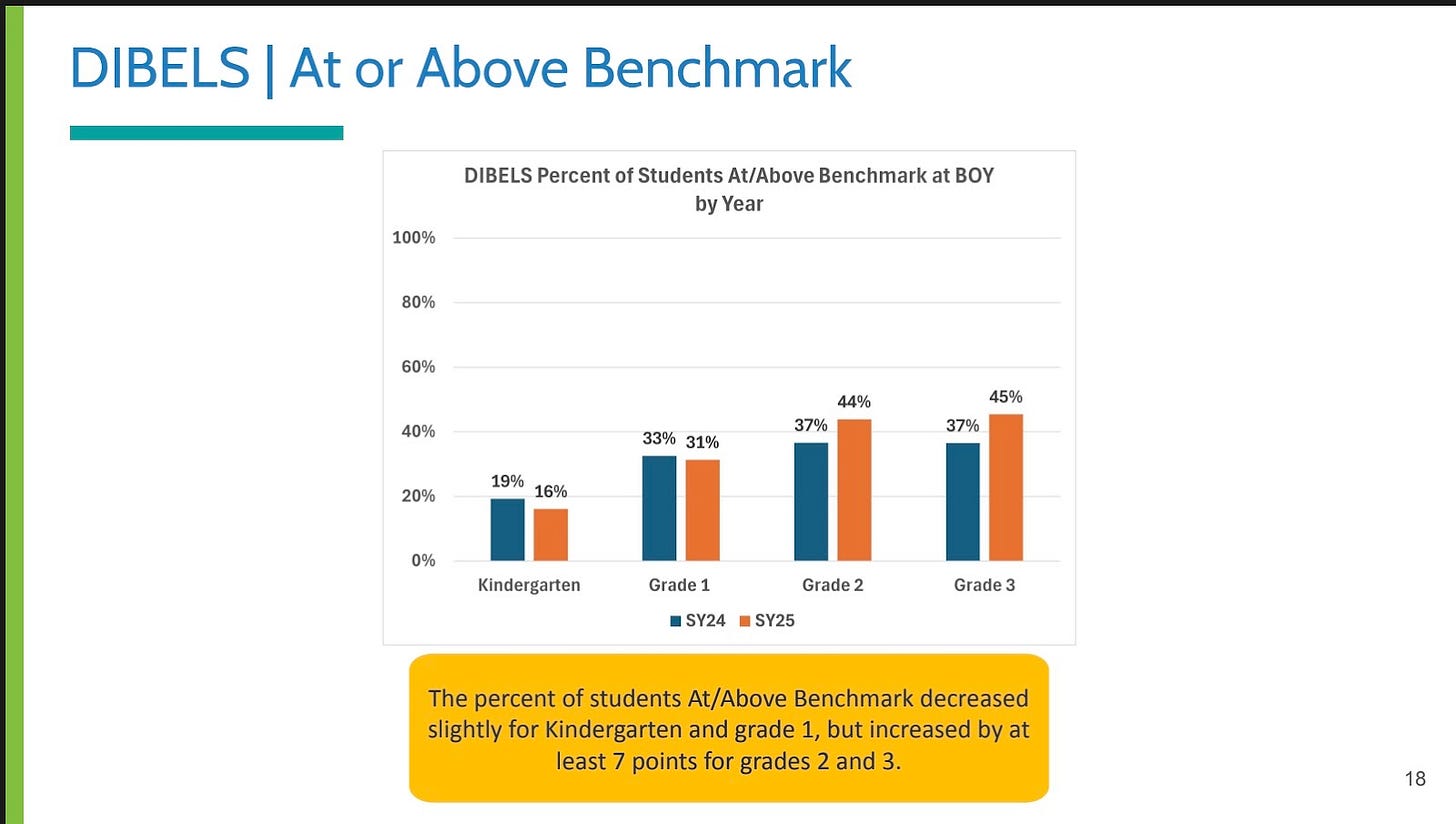

The chart above compares the benchmark status of each grade at the start of the prior school year to the current one. You can see growth for each cohort year. In the class of 2035, who are in second grade this year, 44 percent are at or above the benchmark to start the school year, as compared to 33 percent last year, when they were starting first grade.

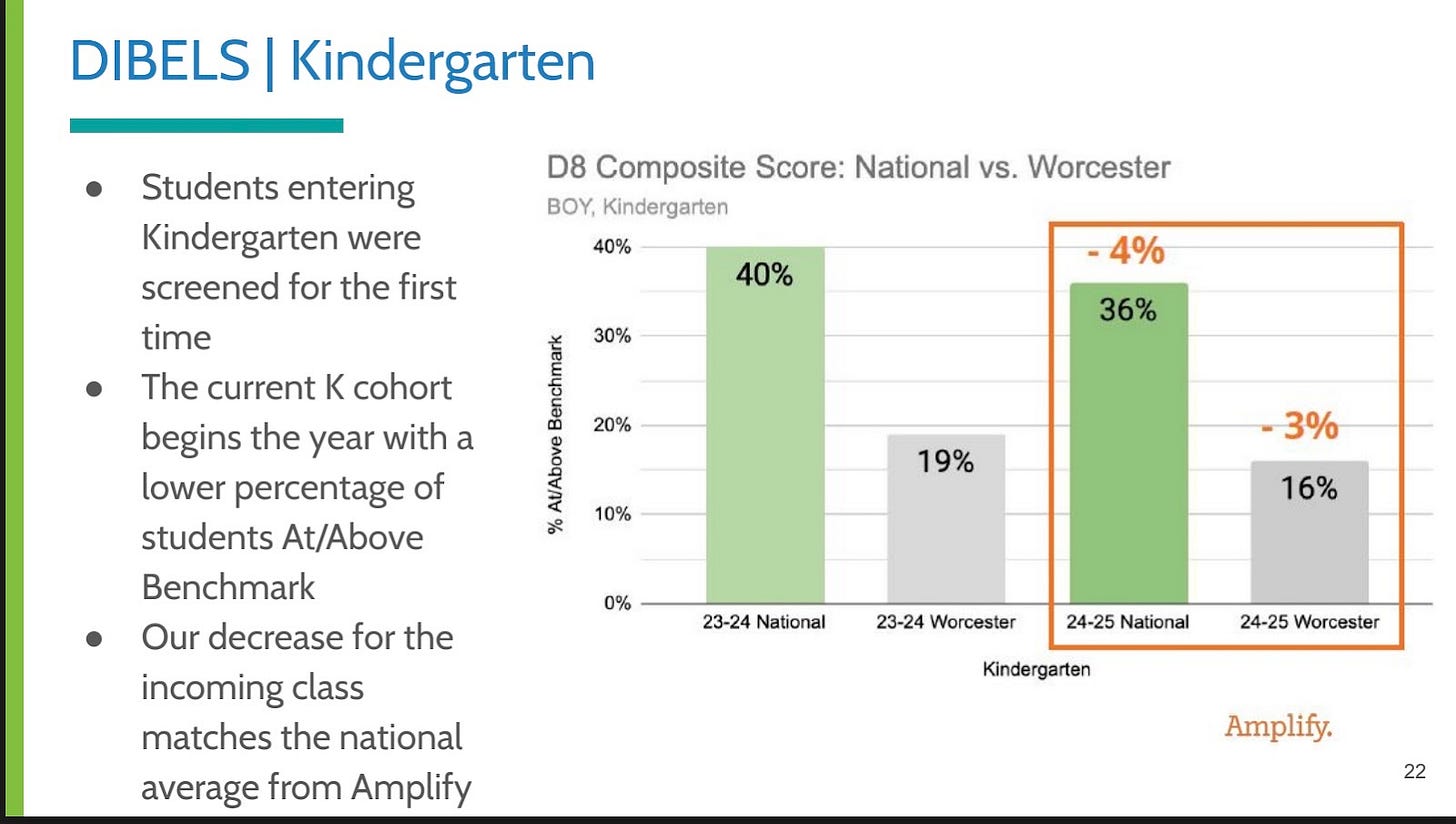

That 44 percent is below the national average of 55 percent, but the growth here is the most important factor when trying to gauge how effective a school system is. WPS is seeing huge growth over last year for the younger elementary age. This is especially impressive when we consider that our kindergartners come in with English literacy skills way below the national average:

For kindergartners at the start of the school year, there is a huge gap between Worcester and the national average, highlighting that the district has a gargantuan task of catching students up from the starting line. This underscores the critical need for high quality preschool for all of Worcester’s kids. When I spoke to principals and teachers they stressed this point: If we want students to do better in literacy we need to start from birth and focus on the 0-5 age range. Only 7 percent of current kindergartners in Worcester were in center-based preschool more than 20 hours a week, and 38 percent were in either a center-based program or a licensed daycare less than 20 hours a week. That means for the other 55 percent, kindergarten is their first time in any formal school. In January, Governor Healey announced a universal pre-k initiative for gateway cities that, by the end of 2026, would give all four-year-olds in Worcester the opportunity (at no or low cost), to enroll in a preschool program. I have not heard any details on how that will be implemented in Worcester. But if we want to advocate for literacy as a community, concentrating on the availability of preschool to Worcester’s four-year-olds is probably the most effective thing we can do.

There’s another reason WPS kindergartners are below the national average: One-third of students in each grade are younger than the vast majority of kindergarteners across the country and the state. Worcester has a kindergarten cutoff of December 31, where in almost all other districts the cutoff is in late August or early September. We are asking four-year-olds to meet state standards set for five-year-olds. And that developmental gap does not necessarily go away as kids get older. In fact, in NYC, where the cutoff is also December 31, kids born in November and December are much more likely to be classified with learning disabilities.

As Lora Barish, a special education teacher at Woodland Academy, told me, “Everything we do in school measures them against grade level, not age. When they don’t progress as a typical kindergartener should, it sets people up for problematic conclusions like getting worried when a four year old isn’t reading. Our MCAS and Star scores are comparing our students to students in other districts that are literally one year older than them. It’s not developmentally aligned.”

Suzanna Resendes, principal of Worcester Dual Language Magnet School agrees. “We’re putting four-year-olds in kindergarten with the expectation that they master literacy skills meant for five-year-olds. Those are really high standards within the developmental age. With four-year-olds we should be focusing on how to share, how to play, words of social emotional health, coping strategies. Instead we’re hoping four-year-olds master later developing skills.”

Changing the age cutoff to September isn’t simple—it would have budget implications and there is an argument that getting kids into WPS earlier is better for them. As the Telegram reported back in 2011, the ideal solution is to bring back full-day preschool, but the district often cites cost and available classroom space as limiting factors. (The city bought buildings in the Elm Park neighborhood when Becker College closed in 2021. At the time the intent was to use some of them for WPS since they are more updated and in closer proximity to more school-aged children. But unfortunately, it sounds like the city is going to sell them.)

So despite kindergartners scoring way below average when they enter WPS, the DIBELS data, which are the discrete reading skills, do not point to a crisis in Worcester—although there is definitely room to improve. Let’s take a look at Star testing, which looks at reading achievement data. It’s a broader review of how children are reading at grade level. Below are the Star data from the end of last school year, in June 2024:

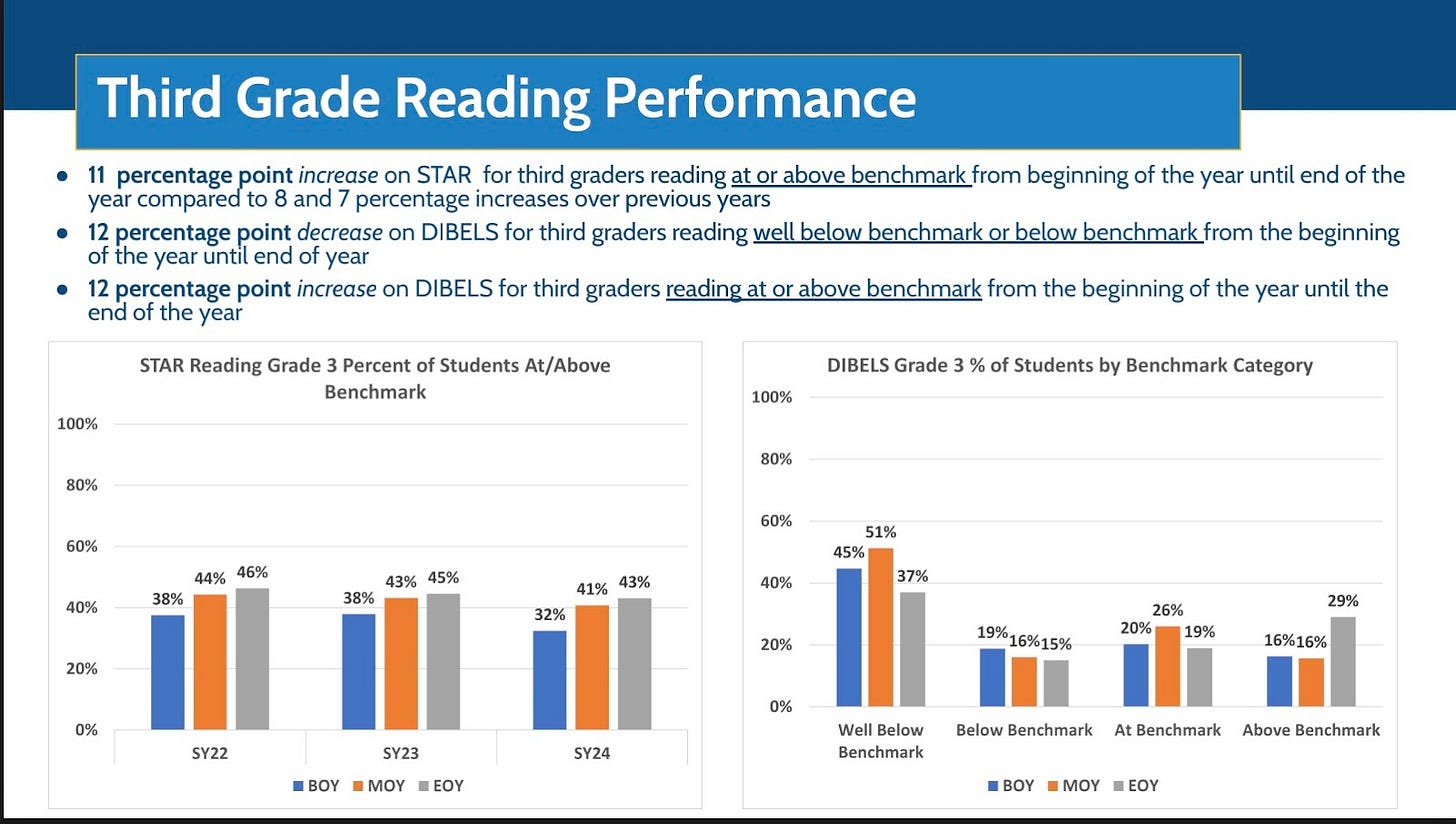

The third graders in this cohort are the class of 2033. They started kindergarten virtually in the fall of 2020. Worcester saw growth in the percentage of students reading at benchmark by the end of the school year, which is great. But as we see over and over again in the “pandemic cohort,” only 43 percent were reading at or above benchmark at the end of year, compared to 46 percent of the class of 2031 at the same age.

It’s clear that the students who need the most support are in this pandemic cohort, the current 4th through 7th graders. What researchers have found works for this group is targeted intensive tutoring or high-dose tutoring, but both require time and money. And sometimes, as teachers have told me over and over, it feels like there just isn’t enough time in the day (which for Worcester elementary schools is actually true. Worcester elementary schools have the shortest school day at six hours, compared to surrounding towns’ six and a half).

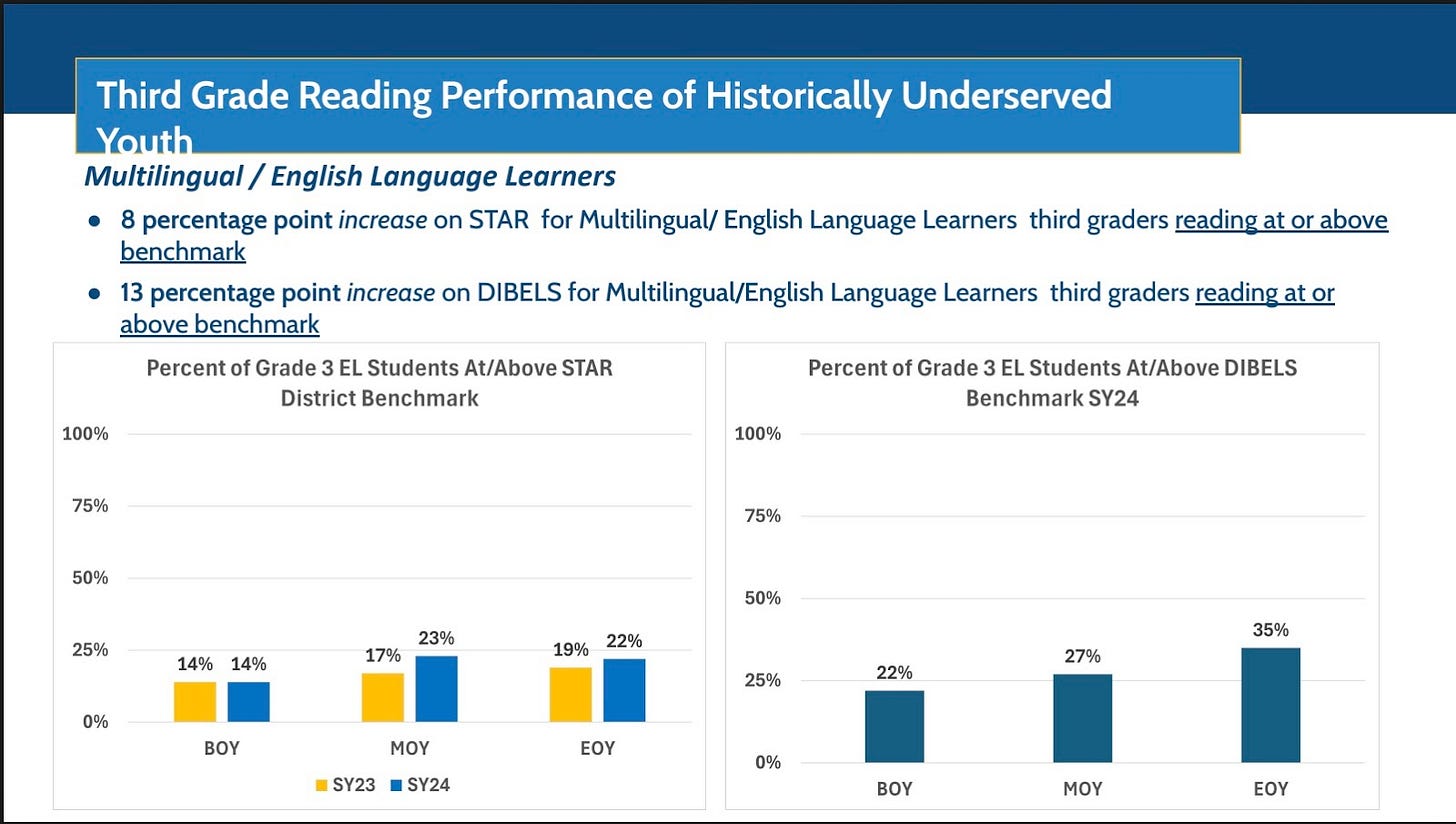

One of the lowest scoring groups on the Star assessment are English learners—something I will return to later—but the group is seeing growth. Currently, there are 4,905 total English learners in elementary school in WPS, roughly about 39 percent of all K-6 students. The Star test only gives part of the picture, as research shows that students with strong literacy skills in their first language, regardless of what it is, are quicker to master literacy skills in English. And quicker is relative, as it takes about five to seven years to achieve academic fluency in English. Without a strong foundation in their native language, it takes students more like seven to 10 years. Assessing students in their native language would give the district a better understanding of how many of those students have a literacy gap, or if it is just an English literacy gap. While assessing students in every native language in Worcester would be challenging, the top two languages spoken in the district, Spanish and Portuguese, already have assessments available.

The takeaway from these data is that the growth in the district is promising. And that we’re doing about the same as districts with similar demographics. Test scores are reflective of so much more than just in-school learning. Campos, who in addition to teaching second grade, is a parent of two elementary students in WPS, emphasized this: “I see that what my students can do in the classroom on a day-to-day basis is not always reflected on the Star tests. Personally, I see that my son’s academics and report card grades do not match his Star scores. I think Star and MCAS, as well as DIBELS, need to be taken with a grain of salt.”

Barish agrees. “These assessments test certain things, but don't show everything a student learns throughout the year. People need to consider the challenges students might be facing before they get alarmed about a score. For example, expecting students to do tasks that are not developmentally appropriate, their status as an English language learner, the effect trauma has had on them, parent involvement, etc.” Barish’s point asks us to consider what is actually happening in the classroom, tempered with elements outside of the school’s control.

What all this assessment data show is that Worcester is not in a literacy crisis, but there are improvements that can, and are, being made to support students to gain even more literacy skills. We are in a hopeful time for Worcester Public Schools. With Superintendent Rachel Monárrez, our school district has a dynamic, talented leader, who has brought in families and community in a way no one has before. She is changing the capacity of what we think is possible and raising expectations. We are also in a monumental shift of how Worcester’s students are spoken about in public discourse, which has traditionally been a “deficit-based” model of thinking; the idea that because Worcester’s students do not fit the dominant perception of what “achievement” looks like, we need to “fix” them. Now when I speak to educators and parents, there is a feeling of transformation, of hope.

And so I have been wondering, how can Worcester take that hope, that engagement, and work as a community to help our kids meet those high expectations now? Worcester has a lot of knowledge and resources in many sectors: institutions of higher education, non-profits, government, but not yet a truly organized effort to work toward the same educational goals. Thus the “solutions” around literacy that politicians and non-profits offer tend to be bandaids like summer reading, book giveaways, or yet another forum. Those are well-intended, but not necessarily effective. How can we all get on the same page, and make sure the time and money we are investing—both inside and outside of school—will make the biggest impact on our district? What is our literacy vision for Worcester Public Schools students? How can we make sure our kids are getting the best education they can?

We’ll explore some of the answers to those questions in part two of this series.

Read part two here:

Thank you for reading. Again, this work is supported exclusively by the paid subscribers of this newsletter! For the price of a coffee a month you can help us grow the real grassroots outlet the city needs.

You can also tip Aislinn directly. She earned it with this one I say.

And help us get the word out!

Thanks again. —Bill

If you want to get your child’s Star assessments emailed to you, you can log in to Clever, the WPS student access point, and click on the Renaissance app. If you scroll to the bottom it says “for parents/guardians, get email updates.”

Excellent, excellent piece of long-form journalism on this topic. Excellent deep dive. Brava.

Great work! Thanks for doing it, Aislinn D, and Bill, for publishing it